By Jim Ewing. Special to The Clarion-Ledger

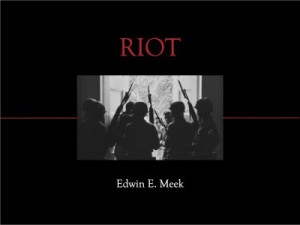

Readers who pick up the large format book of photographs RIOT: Witness to Anger and Change should be prepared to be stunned and horrified. It graphically ushers the unwary into a world of violence and hate that could only have been captured by someone who was there during the racial madness when James Meredith became the first black student admitted into the University of Mississippi in 1962.

Readers who pick up the large format book of photographs RIOT: Witness to Anger and Change should be prepared to be stunned and horrified. It graphically ushers the unwary into a world of violence and hate that could only have been captured by someone who was there during the racial madness when James Meredith became the first black student admitted into the University of Mississippi in 1962.

The narrative is revealing both in its raw honesty — as captivating as the photographs — and its nuance. It begins with Meek’s account. He was a 22-year-old Ole Miss staff photographer when the protest turned violent. He took more than 500 photos throughout that night and the next day, which form the book’s basis.

“The riot began at dusk,” Sept. 30, 1962, Meek writes. “Bottles flew by me to strike federal marshals. Tear gas canisters were fired into the crowd. Bricks smashed into windshields and cars were set on fire. … bullets were flying. Snipers were on top of Bryant Hall, the fine arts center, and on the roof of the old Y building firing at the marshals. I counted a dozen bullet holes on the pillars and door facings of the Lyceum.”

The shots, bricks and mayhem was not at the hands of students, but from thousands of outsiders flooding in.

When it was over, two people were dead, hundreds were injured or arrested. But, added journalist and author Curtis Wilkie, who was a student at the time and writes a superb introduction to the book, “the reputation of Ole Miss was gravely wounded.”

RIOT is a well-crafted book that could stand alone with its stunning photography but it is immeasurably amplified by the insightful commentary by witnesses to the cataclysmic events. The photos are especially compelling as snapshots of a time and place that seems incomprehensible to today — or, perhaps, in some ways, chillingly not.

For example, in one sequence of photos, Meek captured scenes of a football rally the evening before the riot that appear as some bizarre KKK nightmare. In them, a cheerleader rallies the crowd before a giant bonfire and, in another, smiling majorettes wave a large Rebel flag as the band plays behind them. It was all wrapped up, football, politics and “winning” in one broad cloth.

As Wilkie recounts, at that rally, “the state was basically on a war footing and for the first time, the little miniature Confederate battle flags were brought out and distributed to the crowd.”

At the game itself, Gov. Ross Barnett addressed the crowd at halftime, extolling states rights and calling on every Mississippian to stand up to the federal government.

In the moments before the actual rioting begins, Meek recounts, a student played “Dixie,” another dressed as a Confederate soldier brandished his sword. “It felt like a pep rally until I heard the hiss of a bottle sailing over my head and saw it strike a marshal’s helmet,” Meek writes. A television station in Jackson was also cheering for action, calling “for Mississippians to take up arms and travel to Oxford.”

The reminiscence of Meek, who went on to become an assistant vice chancellor and professor, for whom the Ole Miss Meek School of Journalism is named, is particularly personal and revealing.

“I grew up in Mississippi, a segregated society where African-Americans were virtually enslaved as second-class citizens,” he writes. When the National Guard showed up at Ole Miss, he adds, “they were as conflicted as I was.” But he was “about to be brought to terms with my previously unexamined racism.”

Ole Miss alumni or supporters shouldn’t expect any sugar coating from RIOT. While the event is “not remembered with pride at our alma mater,” Wilkie writes, RIOT is “an indelible reminder of our past.”

“To the school’s credit, Ole Miss has never tried to whitewash the story. … The University of Mississippi confronted and eventually came to terms with the traumatic events,” he said, proactively seeking to champion diversity and racial healing. It’s a story that should not be forgotten, lest it be repeated.

As former Gov. William F. Winter said in RIOT’s afterword, courageous trailblazers like Meredith and slain Jackson civil rights leader Medgar Evers are owed a debt of gratitude by all Mississippians.

“They freed us, too. All of us, black and white alike, had been victims of a cruel system of apartheid that kept us all enslaved,” said Winter, an Ole Miss alum who helped found the William Winter Institute of Racial Reconciliation at the university.

RIOT should be on the coffee table of every Mississippian, as a reminder of where we came from and where we need to go. And it should not only be displayed, but read, studied and remembered.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion-Ledger, is the author of seven books including Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them, in stores now.

Comments are closed.