By Jesse Yancy. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (January 26)

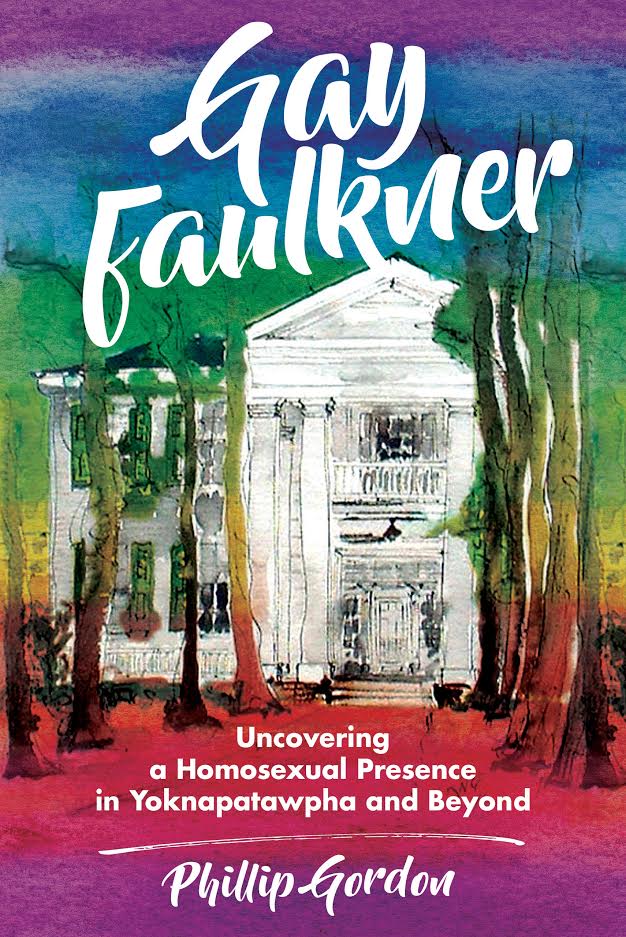

In Gay Faulkner, Phillip Gordon examines Faulkner’s interactions with gay men, his immersion in gay subcultures, especially during the 1920s, and his strong and meaningful relationships with specific gay men, particularly his lifelong friend Ben Wasson. Gordon’s study concentrates on As I Lay Dying and the Snopes trilogy with particular emphasis on Darl Bundren and V.K. Ratliff. Gordon states flatly that “the question at the heart of this study is not ‘Was Faulkner gay?’ . . . what this study really seeks to address: Is there a gay Faulkner?”

In Gay Faulkner, Phillip Gordon examines Faulkner’s interactions with gay men, his immersion in gay subcultures, especially during the 1920s, and his strong and meaningful relationships with specific gay men, particularly his lifelong friend Ben Wasson. Gordon’s study concentrates on As I Lay Dying and the Snopes trilogy with particular emphasis on Darl Bundren and V.K. Ratliff. Gordon states flatly that “the question at the heart of this study is not ‘Was Faulkner gay?’ . . . what this study really seeks to address: Is there a gay Faulkner?”

Gordon seeks to reveal a gay presence not only in Faulkner’s work, but also in his life as well, establishing Faulkner’s awareness of homosexuality and homosexuals, and his acceptance and participation in gay culture. While Gay Faulkner is a solid academic work the notes are as absorbing as the text, and the bibliography constitutes a summation of Queer Faulkner studies. Gordon offers insight, information, and even entertainment for the general reader.

Gordon’s documentation of Faulkner’s stay in New Orleans explores the bohemian atmosphere as well as the writers’ community of the Vieux Carré. Central to this section of the book is Gordon’s account of Faulkner’s relationship with his longtime friend and roommate, the gay artist William Spratling, including an intriguing account of a trip to Italy with Spratling, a journey that resulted in Faulkner’s most openly gay story, “A Divorce in Naples.”

We also discover Faulkner in New York City after the publication of Sanctuary (1931) interacting with the Algonquin Round Table, and his awkward meeting with Alexander Woollcott with his gay friend and sometime agent Ben Wasson and the New Orleans-born gay writer, Lyle Saxon. Gordon describes Faulkner touring Harlem’s gay clubs and cabarets with Carl Van Vechten, where he attended a show by the famous drag “king” Gladys Bentley. This encounter as recounted by Wasson becomes a focal point for establishing the critical importance of the Blotner Papers at Southeastern Missouri State University, which Gordon calls “fascinating, complex, and, for lack of a better word, beautiful.” And despite his earlier disclaimer concerning Faulkner’s personal proclivities, in somewhat of an aside Gordon also avers that “there is evidence in the Blotner papers that suggest our understanding of Faulkner’s sexuality might not be what we have generally assumed.”

Gordon frames Faulkner within the literary milieu of early 20th century Mississippi, which by any standards constitutes the cutting edge of the Southern Renaissance in American literature and includes several prominent gay writers. The queer planter, poet, and memoirist William Alexander Percy of Greenville nurtured a clutch of writers, including Hodding Carter, Walker Percy, Shelby Foote, and Wasson. Gordon also illuminates Oxford’s fascinating and cosmopolitan Stark Young as well as the undeservedly obscure poet and scholar Hubert Creekmore of Water Valley.

In a text, Gordon and other queer critics focus on the meaning and nuances of the words used, and amplify their implications. Some readers may think Gordon is reaching to make a point, but in the end, the words and their meanings are there for any reader to understand. Gay Faulkner has a great deal to be recommended; it’s interesting, educational and, yes, entertaining. It is also a much-needed blade to cut the hide-bound conventions surrounding Faulkner and his work.

Jesse Yancy is a writer, editor and gardener living in Jackson.

Phillip Gordon will be at Lemuria on Thursday, March 26, to sign and discuss Gay Faulkner.

Comments are closed.