Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 22)

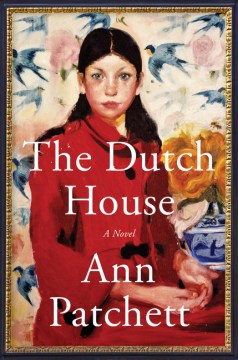

New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett’s seventh novel The Dutch House is a tale that lingers long after the final page.

New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett’s seventh novel The Dutch House is a tale that lingers long after the final page.

A story of home, love, disappointment and forgiveness, the novel centers around the family home of siblings and parents through decades of their changes, longings and, eventually, a comfortable sense of healing that bridges to the next generation.

A graduate of Sarah Lawrence College and the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, Patchett has won numerous awards and fellowships, including England’s Orange Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award. She has authored six previous novels, three books of nonfiction, and a children’s book.

In November, 2011, she became co-owner of Parnassus Books in Nashville, where she lives with her husband, Karl VanDevender, and their dog, Sparky.

Reviews for The Dutch House often refer to it as “a dark fairy tale,” and, indeed, its main characters–two siblings whose childhoods were darkened by the abandonment of their mother, followed by the presence of a cruel stepmother, and their attachment to a large and looming home–spend their lives lamenting their misfortunes in later years, but are still drawn back to the house. Tell us briefly about their childhood regrets.

Danny and Maeve regret that they didn’t get the house. They regret that their stepmother won, and they lost. Funny, but when I think about regrets, I tend to think about my own actions and not the actions of others. I think they see themselves as fairly blameless in how the events of their childhood unfolded, and I think they’re right. I don’t want to give too much away but when Danny is a teenager, he feels he dealt with a terrible situation terribly, but I believe that as an adult he doesn’t blame himself or harbor any regret.

The house that siblings Maeve and her younger brother Danny grew up in–and would be banished from–is practically a character itself. The design and features of this unique structure, not to mention its furnishings–loom as large as its physical presence. In what ways does this house stand as a metaphor of this story?

Ann Patchett

I think of houses as our public face. Our house is how other people see us. Houses represent our success and our failure, our good times and bad. It’s where we store our memories. If you’ve ever had the experience of driving past a house you used to live in, you remember very quickly how you felt when you were there. So, for Danny and Maeve, the house represents a happier time when their mother was still with them, and it also represents the security of wealth. They had never imagined another kind of life for themselves, and while Maeve was already out of the house, and in a very small apartment, Danny had no idea about the turns that life might take. Children rarely do.

The story goes far beyond the siblings’ childhood years, continuing through their middle age and beyond–as it unfolds their divergent careers and personal lives, and, near the end, the unexpected appearance of a character. When you’re developing a story, do you map out the way their lives evolve for such a long time?

I do. Different writers approach this question differently. I really have to know where I’m going, or I just meander around and get nowhere. I like structure and plot, so I work out the larger details of the novel before I start writing. It’s my favorite part of the process, thinking a story up. I don’t write things down. I keep everything in my head. That way I don’t get too attached to a certain idea. I can change my mind. I can just forget about something. My outlines aren’t specific, but I have a clear idea about all the characters, who they are, what they want, as well as their arrivals and departures.

It seems that the Dutch House redeems itself at the end. What does that state for the entire story?

I’ve been told this is a very sad book and I’ve been told it has a happy ending. I like the fact that different people can read it in different ways. The house never changes. It is, after all, just a house. It’s incapable of feelings, a fact that irritates Danny and Maeve who believe on some level that the house should have collapsed in solidarity when they were thrown out. Again, I don’t want to give anything away. Let’s just say the house is loved and obsessed over for many generations.

Ultimately, this story doesn’t seem to be the expected “good guy, bad guy” tale; rather, it’s pretty much everyone doing the best he or she can. Could you comment on that?

I’m awful at writing villains. I definitely lean towards sympathetic characters, mainly because most all of the people I know personally are sympathetic. We seem to be living in a world of good and evil now, and who is good and who is evil depends on who you’re listening to. But I think most people do the best they can. That said, Andrea is the closest thing I’ve ever come to a villain, and I can even see how she was young and in over her head. I keep meaning to try harder with my villains, but I spend so much time with my characters and look at them so closely I can’t help but feel some empathy for most of them.

Lemuria has chosen The Dutch House as its September 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

Comments are closed.