By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 12)

In fiction, it’s not uncommon for an author to go back in time to solve a mystery, often with shocking results. Less common is for a nonfiction book to do the same, but with a searingly honest view that’s sadly revealing today.

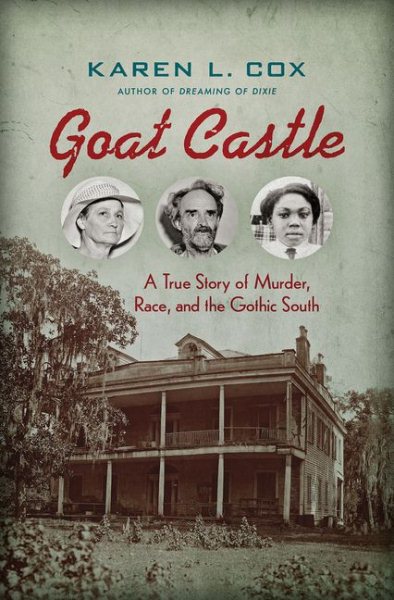

Karen L. Cox does so with her book Goat Castle (University of North Carolina Press).

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time.

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time.

Subtitling the book “A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South,” Cox details the lurid aspects of the case that transfixed the nation with its depiction of a South in ruins and the remnants of Southern aristocracy in squalor in the decades following the Civil War.

The headlines of the time focused on Merrill, called an aging recluse, allegedly killed by a black man and her black housekeeper, with her white neighbors as possible accomplices.

The neighbors lived in a falling down mansion they shared with goats and other livestock wandering the halls (hence, the name “Goat Castle”).

“Murder, aristocracy, recluses, and goats,” Cox notes, “these were the subjects more likely to be found in a Southern Gothic novel, and in fact journalists immediately drew parallels to the fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, and later, William Faulkner’s novels about the social decay of old Southern families.”

It was the type of news story that kept Depression-era Americans grossly entertained.

But Cox dives deeper than the headlines, through excellent historical and journalistic investigation, to bring to light a horrible injustice.

Whereas, Merrill’s white neighbors, Dick Dana and Octavia Dockery (she, the daughter of a Confederate general; he, of a family of a famous authors and journalists) got off scot-free, the two black suspects were either killed or imprisoned.

Cox details the lives of Merrill and her alleged paramour and cousin, Duncan Minor, who discovered her body. And she recounts the often bitter and ongoing disputes of the aristocratic Merrill with Dana, called the “Wild Man” who was known to wear only a burlap sack while living in the trees on his property, and Dockery, called the “Goat Woman,” who was glib, clever, and vengeful, albeit living hand to mouth.

The new knowledge of the case is Cox’s painstaking research into the lives of the two black suspects, Lawrence Williams, the alleged triggerman who was gunned down in Arkansas while making his way home to Chicago, and Emily Burns, who received a life sentence at the notorious Parchman Prison farm at Camp 13–the Women’s Camp.

Burns’ sentence was indefinitely suspended after eight years because even in the Jim Crow South that saw black men imprisoned or killed for allegedly improperly looking at a white woman, Gov. Paul B. Johnson Sr. said he was “thoroughly convinced of (her) innocence” and that she was convicted solely upon “circumstantial evidence.”

As Cox details, Burns’ treatment was based on a coerced “confession” and included the belief that unless someone was held accountable for the crime in a court of law, white citizens might have taken matters into their own hands and she might be lynched.

“Emily was presumed guilty because of her race.”

Filled with astonishing photographs and copious notes, Goat Castle is sure to invite attention anew to an old crime in the Bluff City and reinvigorate current debates about racial justice.

Jim Ewing, a former Clarion-Ledger writer and editor, is the author of seven books including his latest, Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them.

Karen L. Cox will appear Wednesday, November 15 for the History is Lunch series at the Old Capitol Museum at 12:00 p.m. She will appear at Lemuria at 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday to sign and discuss her book, Goat Castle.

Comments are closed.