Category: Staff Blog (Page 9 of 32)

If you have walked outside recently you know that it is definitely summer in Mississippi again- and I couldn’t be happier. I love the way the summer smells, I love the long days, and I might be the only one that loves the heat. Spending an entire day outside getting filthy and sweaty is still a real pleasure to me- one I rarely get to enjoy anymore. But there’s also fresh veggies being pushed by a farmer’s market that has made some real strides in making fresh produce more available to people in this city. Fondren had it’s first all day First Thursday last week, which I hope a lot of people went out to support the small but growing group of artists blooming all over the city. If you work in a bookstore or have children of your own you know what the summer is really all about: SUMMER READING!

I loved reading for school and then getting to have a teacher explain the significance of what I just read. Novels became a true love for me with my summer reading books because I learned all books have secrets in them. A single page could contain the right combination of words that unlocks a secret, but this is not just the author’s secret- it is your secret as well. Hidden in that book the author has spoken right to you, to an experience you never knew anyone else felt; but if the author felt it, then it must follow logically that some other reader- somewhere reading those same words as you- knows it too. If we are to join in this community of thinkers and shared experiences we have to start somewhere. A shared library of classics we have all read could be a beautiful way to create a shared experience and understanding.

If that was the best of times, then what was the worst of times? Dull classics that crushed my imagination and frustrated me. When children are nothing more than hormones and imaginations why would you ask them to read The Scarlet Letter or A Tale of Two Cities? These are dense, complex novels with imagery and alliterations I still cannot completely grasp, but I was forced to memorize the details that would be on the tests. The significance of the French Revolution or Puritan morality both certainly went over my head because they were inappropriate for the age group when we read them. It is a mistake to show children these books as the benchmark that other books are to be measured by. For many students these will be the only books they read that year and if you hated every book you read in a year you would stop reading until you were forced to read again, just like most students.

If that was the best of times, then what was the worst of times? Dull classics that crushed my imagination and frustrated me. When children are nothing more than hormones and imaginations why would you ask them to read The Scarlet Letter or A Tale of Two Cities? These are dense, complex novels with imagery and alliterations I still cannot completely grasp, but I was forced to memorize the details that would be on the tests. The significance of the French Revolution or Puritan morality both certainly went over my head because they were inappropriate for the age group when we read them. It is a mistake to show children these books as the benchmark that other books are to be measured by. For many students these will be the only books they read that year and if you hated every book you read in a year you would stop reading until you were forced to read again, just like most students.

I am very happy to see more contemporary/popular books on summer reading lists these days. I think the only way to get children to become readers is to show them how much fun it is. Reading can be an amazing escape from the stresses of growing up, it can expand your way of thinking, it can nourish you and connect you and make you feel loved. We have to show young readers where to find the books that will do just that for them. Where can we find a middle ground from these two opposing views I put forth? I think it must be in a diversity of books we have all read and are able to relate to. Asking children to read dusty old classics is sure to bore them away from a love of books- but we can nurture that love with a selection of books that are appropriate in content and relatable to the culture they know.

I am very happy to see more contemporary/popular books on summer reading lists these days. I think the only way to get children to become readers is to show them how much fun it is. Reading can be an amazing escape from the stresses of growing up, it can expand your way of thinking, it can nourish you and connect you and make you feel loved. We have to show young readers where to find the books that will do just that for them. Where can we find a middle ground from these two opposing views I put forth? I think it must be in a diversity of books we have all read and are able to relate to. Asking children to read dusty old classics is sure to bore them away from a love of books- but we can nurture that love with a selection of books that are appropriate in content and relatable to the culture they know.

Every time I eat a blackberry or see a blackberry, I think about Meditations at Lagunitas by Robert Hass. For somebody who loves words, the way they feel in your mouth and the way they look on the page, Hass’ poem is a gold mine of beautiful language and a love letter to the written word.

And then at the end:

There are moments when the body is as numinous

Meditation at Lagunitas

By Robert Hass

A book recommendation can take the form of a business card. When speaking about the book world to a friend, acquaintance, or even a stranger, it is easy to convey a recommendation. And, like a business card, a book recommendation only actuates its potential when received by another—so readers give out recommendations freely. There is no obligation to those that receive the suggestion to go to Lemuria and make a purchase; a recommendation and a business card are gestures of self-expression. With both recommendations and business cards, the action can be interpreted as, “Hi! This is my name and this is my interest (or product/service). And, I would like to share this with you!” It is then up to the receiver to seek out the interest, product, or service on their own time. It is a closed circuit, totally reliant upon the receiver to manifest the gesture of the recommender’s self-expression toward heightened levels of understanding, appreciation, and interaction.

However good it feels to hand out a recommendation, there is always the lingering possibility that the recommender is just stating, “This is who I am, and this is what I like.” A recommendation is merely the skin of the apple a book worm wishes to wiggle through. A book worm wants to put a book they truly care about into the hands of a person they truly care about. Unlike a mere recommendation, lending a book to someone is reticent of a specific type of trust: the receiver is obligated to actually read the book, and the lender is obligated to be sure that the receiver will find some sense of mutual interest or identification with the work. Lending your favorite book to a complete stranger is like going to third base on a first date, probability points towards mutual regret and a hope that you can get your hands on one of those red flashing lights from Men In Black. Once you lend out your favorite book, you can’t just ask for it back after a day or two of missing it, just like you can’t just take off your beer goggles and get your standards back.

This is an anecdote of the time I went to the proverbial third base (as far as book lending goes) on a first date. Chance proved probability wrong: I rolled the dice and hit sevens four times in a row.

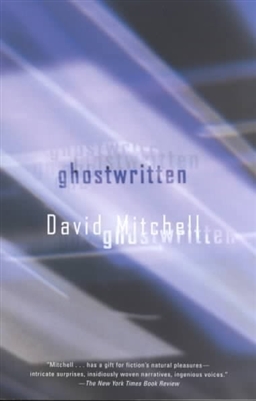

The book in question is Ghostwritten by David Mitchell. My sister, who has consistently supplied me good reading material for as long as I can remember, bought a copy of Ghostwritten from Lemuria for my college graduation present. At the time, Mitchell was an author I’d never heard of and didn’t pick up his book right away—that is until I watched the movie Cloud Atlas and noticed Mitchell’s name as writer in the credit reel.

The book in question is Ghostwritten by David Mitchell. My sister, who has consistently supplied me good reading material for as long as I can remember, bought a copy of Ghostwritten from Lemuria for my college graduation present. At the time, Mitchell was an author I’d never heard of and didn’t pick up his book right away—that is until I watched the movie Cloud Atlas and noticed Mitchell’s name as writer in the credit reel.

The air conditioner in my apartment wasn’t working the day I read Ghostwritten but I wasn’t sweating because it was mid June in Mississippi—but because I was hurtling uncontrollably at unfathomable speeds through time and space toward the ultimate culmination of Mitchell’s first published novel.

I devoured it in one sitting; skipping lunch and dinner, I let my fingers touch every page and let my eyes touch every word. I had an instant connection to Ghostwritten and to David Mitchell. The simultaneous diversity and parallelism of the ethnically, sexually, and geographically dislocated narratives was unlike any other work I had read before.

I believe the romance between the lines of Ghostwritten’s prose brings forth an ephemeral observation that proves an interconnectedness of human consciousness that blurs the line between the physical and metaphysical. At the same time it sought a delicate manifestation of spirituality; Ghostwritten hooked me with a science fiction climax that could give any die-hard Trekkie goosebumps.

So, as my anecdote goes, I decided to lend it to a friend of a friend who I had met for the first time after a night at the pub. I wanted someone, I wanted anyone to connect with this work in the way I did.

Weeks turned into months, and months turned into a year, and I hadn’t received any word that the person had read any of the book. I kept telling friends all about Ghostwritten, each time fighting of a relentless urge to tell them how it ends—and one after another, maybe sensing that I really did love this book—would ask me to borrow it. I cursed myself for having thrown it into the wind on a one night stand.

Then it happened, and when it happened it made complete sense. I was at the same pub where it was given away, talking to a friend who was out for the first time after a minor surgery. As many of my late night conversations go, it took a deep philosophical turn. But then, all the sudden she decided to interrupt the conversation and said, “You know what? I have a book you might like.” She reached into her purse and pulled out the most raggedy paperback book I had ever seen. The cover was missing, and binder clips held pages together where the glue had dried up. She says, “Its called Ghostwritten, its by the same guy that did that movie Cloud Atlas.”

I tried my best to stifle squeals of hysteria, but failed, and by the expression on her face I could tell I needed to calm down. Instantly I asked what she thought about this part how it subtely connected to this other part. I was hardly giving any time for a response.

Then…

She told me that a mutual friend brought it to her after his grad school semester in Oklahoma. So, the next day, I called the mutual friend in Oklahoma to see what he thought of Ghostwritten, and I learned that another mutual friend had lent it to him while visiting in Mexico. That evening, I made an international call to the other mutual friend in Mexico, to see what he thought of the novel. For a moment, he forgot the authors name and exclaimd, “Oh yeah! I remember now, I’d never heard of the author before, but I thought it was really cool. It was on my roommate’s shelf.” I asked, “So who’s your roommate?” I was robbed of all conversation skills when he told me that the roommate was one and the same person as the friend of a friend that I had lent the book to originally.

As if in a profound physical realization of the dislocated, parallel narratives in Ghostwritten, the book passed from hand to hand, over borders, and across nations—all in order to return to its point of origin. I feel as if the connectedness embodied by Mitchell in his first work, lifted off the page, defied reason and geography and proved to me, first hand, the dogmatic connectivity of humanity. Ghostwritten spearheaded through my heart with such grand momentum, it carried itself through the hearts of at least four others without encouragement from me.

Ok, so this book has nothing to do with Barbara Streisand, but it does feature a beautiful woman with wit to spare, and confidence enough to rise to stardom when no one takes her seriously. So, ya know, same thing. Minus the musical numbers.

If you were expecting a novelization of the classic movie musical, like almost everyone who has seen the book on my shelf, you may be disappointed at first. But only at first. Nick Hornby’s story takes you back to the 60s and into London, introducing Sophie Straw, a bombshell who could do just fine for herself as a pretty face selling perfume or even modeling. But obviously that’s not enough for her. She knows how funny she is and has only one goal in life: to be the English Lucille Ball. Who knew being so pretty could get in the way of being so funny? On her push to fame, Sophie meets producers, writers, directors, a huge cast of characters all setting Sophie up for her next big gag.

For anyone who laments the current reality TV trends and longs for the bygone beauties of classic small screen, this book is for you. Reading about Sophie’s failures and triumphs in auditions, her interaction with writers and directors, you can almost hear the live studio audience laughing in your ear. There were moments that made me feel as if I were watching I love Lucy re-runs or some other sit-com that Sophie would have killed to be cast in. Sophie’s passion and confidence aren’t unlike other girls you’ve seen in these shows, but her quick wit and sharp banter make reading the behind the scenes stuff just as fun. The dialogue between characters is part of what sells the sit-com feel of the novel. While some of the characters lack a little individuality, most play a supporting role to Sophie in the spotlight and make her shine even brighter. As her story progresses, we are treated to a look at how careers in the TV industry change over time; Sophie starts as nothing, makes a name for herself, becomes loved by all, and beyond.

For anyone who laments the current reality TV trends and longs for the bygone beauties of classic small screen, this book is for you. Reading about Sophie’s failures and triumphs in auditions, her interaction with writers and directors, you can almost hear the live studio audience laughing in your ear. There were moments that made me feel as if I were watching I love Lucy re-runs or some other sit-com that Sophie would have killed to be cast in. Sophie’s passion and confidence aren’t unlike other girls you’ve seen in these shows, but her quick wit and sharp banter make reading the behind the scenes stuff just as fun. The dialogue between characters is part of what sells the sit-com feel of the novel. While some of the characters lack a little individuality, most play a supporting role to Sophie in the spotlight and make her shine even brighter. As her story progresses, we are treated to a look at how careers in the TV industry change over time; Sophie starts as nothing, makes a name for herself, becomes loved by all, and beyond.

So turn the TV off, pick up Nick Hornby’s Funny Girl and have yourself a few laughs. I promise, the Bachelorette doesn’t need you.

Most of us who are over 20 can point to a few big events that set us on the road to adulthood. For the never-named narrator of M.O. Walsh’s debut novel, My Sunshine Away, it was the rape of his teen crush during her sophomore (his freshman) year of high school, Lindy Simpson. The narrator and Lindy have been neighbors since grade school, during which time he has harbored an innocent, but obsessive love for her. The search for the unseen rapist—who knocked her off her bike and forced her face into the ground—brings all the neighborhood oddballs into suspicion. It also brings the narrator closer to realizing his puppy-like fantasy. Unfortunately, he implicates himself in the process, in multiple ways. During this time, his divorced parents are still acting out their drama, and then his sister is killed in a car accident, leaving no adult—except a loveable but unstable uncle—with time or emotional bandwidth to spare for him as he lurches toward maturity.

There’s no shortage of coming-of-age novels. Among the qualities that distinguish this one is the memoir-like voice of the narrator and the unsentimental, yet forgiving examination of his immature self and his teenage posturing. Now grown and settled, the narrator understands that his actions were at once classic teen behavior and almost invariably the “wrong” thing to do, yet they revealed the true nature of the people around him, progressively peeling away his naïveté.

There’s no shortage of coming-of-age novels. Among the qualities that distinguish this one is the memoir-like voice of the narrator and the unsentimental, yet forgiving examination of his immature self and his teenage posturing. Now grown and settled, the narrator understands that his actions were at once classic teen behavior and almost invariably the “wrong” thing to do, yet they revealed the true nature of the people around him, progressively peeling away his naïveté.

Another quality that lifts My Sunshine Away above the coming-of-age glut is the vivid setting; a white, middle-class subdivision of Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the late 1980s and early ’90s. The kids of Woodland Hills mostly go to the private Perkins School. I grew up in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, a morning’s drive from Baton Rouge. Walsh’s dead-on description of the brutal Louisiana summer stirred nostalgia and commiseration:

You should know:

Baton Rouge, Louisiana is a hot place.

Even the fall of night offers no comfort. There are no breezes sweeping off the dark servitudes and marshes, no cooling rain. Instead, the rain that falls here survives only to boil on the pavement, to steam up your glasses, to burden you.

The ninth chapter is a defense of the narrator and author’s native state that begins: “I believe Louisiana gets a bad rap.”

“We are relegated to a different human standard in the south as if all our current tragedies are somehow payback for our unfortunate past.”

Yes, the state is corrupt, its racial tensions endemic, its floods catastrophic. But there’s the food, the culture, the community. Red beans and rice or seafood po-boys are “small escapes from the blatantly burdensome land.”

This chapter of praise is wonderfully placed within the architecture of the book. Yes, it interrupts the narrative arc, but it also lightens the tone. Like the meals, this chapter offers a break from the bleak subject—a teenage girl’s rape; it doesn’t undo the awful, but it does give us, the readers, a reprieve. Chapter 28, a warm-hearted and evocative comparison of New Orleans and Baton Rouge, plays a similar role after a fraught and literally climactic chapter in which the narrator realizes that he never understood or even really empathized with Lindy’s trauma, so obsessed was he with his own wants.

Defying the literary tendency to define the South by its own history (this isn’t a story about race), Walsh ties the narrative to national events. The narrator traces his love of Lindy to the day of the Challenger explosion when he was in fifth grade. His school had assembled to watch the first teacher in space, only to witness a disaster. In the chaos, Lindy throws up on herself and he offers his shirt, a moment of vulnerability only witnessed by the teacher, his first protective act. And there’s our hero, the narrator, whose potential guilt comes up twice. The first time the police are questioning all young males in the neighborhood, he doesn’t even understand the term rape. He thinks it means to get totally beaten in a game, as in when LSU lost a football game 44 to 3, and someone says, “We got raped.”

The novel’s title comes from a line of the song, “You Are My Sunshine,” written by the late Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis: “Please don’t take my sunshine away.” While the chorus is pleasant and campy, the verses shift toward the sinister: I’ll always love you and make you happy / If you will only say the same / But if you leave me to love another, / You’ll regret it all one day.

The song shows the porous border between love and violence. A man thinks back on himself as a boy who has a crush on a girl and draws pornographic pictures of her. And he thinks about the man who assaulted her and wonders what kept the boy who had the crush and the white-hot yearnings from becoming the second man or someone like him? The clarity of age reveals all.

Plainsong by Kent Haruf. New York, NY: Knopf, 1999.

The simple wisdom of Kent Haruf’s “Plainsong” is revealed in the choral cast of characters. The interwoven stories stay with the reader long after the book is finished: a watchful teacher, a young pregnant girl who finds support from an unexpected pair of lonely bachelor farmers, a couple of young boys making their way without a mother. “Plainsong” is a story about a community coming together when the most predictable lines of support are absent.

The simple wisdom of Kent Haruf’s “Plainsong” is revealed in the choral cast of characters. The interwoven stories stay with the reader long after the book is finished: a watchful teacher, a young pregnant girl who finds support from an unexpected pair of lonely bachelor farmers, a couple of young boys making their way without a mother. “Plainsong” is a story about a community coming together when the most predictable lines of support are absent.

Kent Haruf was born in 1943 and grew up on high plains of eastern Colorado, the landscape that features prominently in all of his novels. A college course in American literature exposed Haruf to Faulkner and Hemingway and changed his aspirations from a biology teacher to literature and writing. After two years living in Turkey as a Peace Corp volunteer, Haruf applied to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop but was rejected. The University of Kansas instead provided a graduate degree but Haruf still longed for the writer’s workshop in Iowa, so he moved to Iowa City in the dead of winter with his wife and baby girl with no placement and a meager job as a janitor in a nursing home. By May, he was finally accepted. It was in Iowa that Haruf developed important writer friendships with Denis Johnson, Stuart Dybek, Tracy Kidder, T. C. Boyle, and John Irving. He also developed his fictional landscape of Holt County, Colorado where all of his novels would be set.

After writing for eleven years, it was his friend John Irving who sent Haruf’s first novel to his own agent at Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Haruf recollects in an essay for Granta: “[Irving] said he had sent fifty writers to his agent and he hadn’t taken any of them, but maybe he’d take me. And he did . . . That was a great day for me.” Haruf had been writing for twenty years and was forty-years-old in 1984 when his first book, “The Tie That Binds,” was published and won a PEN/Hemingway citation and a position teaching freshman composition at Nebraska Wesleyan. Later, he received a more prestigious position at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale where he would write his breakout novel “Plainsong.”

After writing for eleven years, it was his friend John Irving who sent Haruf’s first novel to his own agent at Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Haruf recollects in an essay for Granta: “[Irving] said he had sent fifty writers to his agent and he hadn’t taken any of them, but maybe he’d take me. And he did . . . That was a great day for me.” Haruf had been writing for twenty years and was forty-years-old in 1984 when his first book, “The Tie That Binds,” was published and won a PEN/Hemingway citation and a position teaching freshman composition at Nebraska Wesleyan. Later, he received a more prestigious position at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale where he would write his breakout novel “Plainsong.”

Gary Fisketjon & Kent Haruf / Credit: Ronald M. Overdahl / Staff Photographer for Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

In 1998 Haruf’s agent sent “Plainsong” to Knopf, and Gary Fisketjon became his editor. Besides the intense yet never overbearing editing that Fisketjon offered, the two developed a friendship over part of Haruf’s 15-city author tour. “Plainsong” received a National Book Award nomination as well as adoration from a growing fan base. Fisketjon recalls on his blog, “Remembering Kent Haruf”: “Readers who’d taken so much from his work were now lining up to give something—adoration, trust, celebration—back to him.”

Collecting the six novels of Kent Haruf is to collect something of the heart. The stories of Kent Haruf never leave the reader and it can seem somewhat irrelevant to collect the books as objects. However, the stories are more than just stories that touch the heart. These novels read as modern day classics and will endure as classics. Haruf’s first two novels are harder to find as the print runs were smaller and signings were limited. By the time “Plainsong” was published, the print run had expanded to 70,000 and Knopf sent Haruf on national signing tours. Knopf issued a small number of “Benediction” signed as Haruf was too ill to tour. Kent Haruf passed away November 30, 2014 at the age of 71, but not before leaving us one final gift. “Our Souls at Night” goes on sale May 26, 2015.

Collecting the six novels of Kent Haruf is to collect something of the heart. The stories of Kent Haruf never leave the reader and it can seem somewhat irrelevant to collect the books as objects. However, the stories are more than just stories that touch the heart. These novels read as modern day classics and will endure as classics. Haruf’s first two novels are harder to find as the print runs were smaller and signings were limited. By the time “Plainsong” was published, the print run had expanded to 70,000 and Knopf sent Haruf on national signing tours. Knopf issued a small number of “Benediction” signed as Haruf was too ill to tour. Kent Haruf passed away November 30, 2014 at the age of 71, but not before leaving us one final gift. “Our Souls at Night” goes on sale May 26, 2015.

Written by Lisa Newman, A version of this column was published in The Clarion-Ledger’s Sunday Mississippi Books page.

Ok, let’s talk about sex.

People having been writing about sex, love, and loss for centuries. Recently, I assigned myself the mission of rifling through our stock of erotic poetry here at Lemuria to see what it is that makes poems about sex so damn interesting. Is it the snickering, childish curiosity that moves us, or is it a yearning for the familiarity of human touch, even if it’s from a page?

In haiku, desire is portrayed almost entirely in natural images; flowers opening, the cool rain on hot, dry earth. It is subtle and easy to misunderstand. The words are gentle and soothing. A favorite of mine:

By Yoshiko Yoshino

nights of spring–

tides swelling within me

as I’m embraced

shunya miuchi ni ushio unerite dakare ori

Similarly, the erotic verse of the sixth Dalai Lama relies heavily on natural imagery, but brings an achingly human element to the stories being told. So often the poetry recalls unrequited love or the yearning of . . . being . . . horny.

So out of my mind with love,

I lose my sleep at night.

Can’t touch her while it’s day–

Frustration’s my sole friend.

When I picked up E. E. Cummings book Erotic Poems I had NO idea what to expect. Turns out it is as confusing and tender as his other collections; a combination of jagged, unfinished thoughts, and jarringly familiar moments (i.e., the phrase “don’t laugh at my thighs”). Several times I was caught between “aawwwwww” and “what the hell?” moments. Here’s a favorite that savors strongly of The Song of Solomon:

[my lady is an ivory garden]

my lady is an ivory garden,

who is filled with flowers.

under the silent and great blossom

of subtle colour which is her hair

her ear is a frail and mysterious flower

her nostrils

are timid and exquisite

flowers skilfully moving

with the least caress of breathing,her

eyes and her mouth are three flowers. My lady

And then there’s Jill Alexander Essbaum; poet extraordinaire and April’s First Editions Club author here at Lemuria for her debut novel, Hausfrau. Before Essbaum wrote Hausfrau, she dabbled in erotic poetry and came up with some blush-worthy stuff. Where the Japanese are subtle and coy, she is brazen and honest. Instead of constant natural metaphors, she gets straight to the point, and there is something refreshing and scary about that, if I’m being completely honest. Essbaum pulls a lot of spiritual references into her poetry, pushing the imagery as far as she can possibly go. It is insulting, impossible to put down, and strikingly beautiful. Here is a tamer poem from her collection, Harlot:

Psalm of Shattering by Jill Alexander Essbaum

Oh Lord of Hosts and Nazarenes,

Hear my Psalm of Shattering.

How do I come to feel these griefs?

A little lust is a dangerous thing.

Beneath the orchard canopy

As balm of pear swelled in the breeze

I squeezed his pulse between my knees,

And behaved my hands so shamelessly.

Our eyes belied a hot-blood need.

He stroked my body, crease to pleat.

A passerine purled from the fork of a tree

As he passed his mouth all over me.

But the torture of Christ was shared with thieves.

His was the right cross. The left was for me.

I lumbered up to Calvary

As cloud moved into mystery.

I’m fifty kinds of agony.

And so damn drunk I cannot see.

And so damn sad I cannot breathe.

I meant well, if half-heartedly.

So I laze in a bed of catastrophe,

And sleep these dreams that are not dreams.

I’m guilty of nothing but defeat.

His ardor caroused the unrest in me.

But nothing will rouse the rest of me.

This blog was about two weeks in the making and I still feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of what I was looking for or even found what I was looking for at all. I guess I’ve always known that not all erotic poetry is the same, and that I’m enormously uneducated when it comes to poetry in general. What I have figured out is that there is so much beauty in erotic poetry. Maybe it was my upbringing in the the church, hiding under pews and trying to figure out the infinite mystery of sex that was handed to me in The Song of Songs, but I know in my heart that poetry about the intimacy between two people can be a very spiritual thing. To connect with another human, even on the page; that is a kind of fulfillment that everyone deserves.