By Matthew Guinn. Special to the Clarion-Ledger.

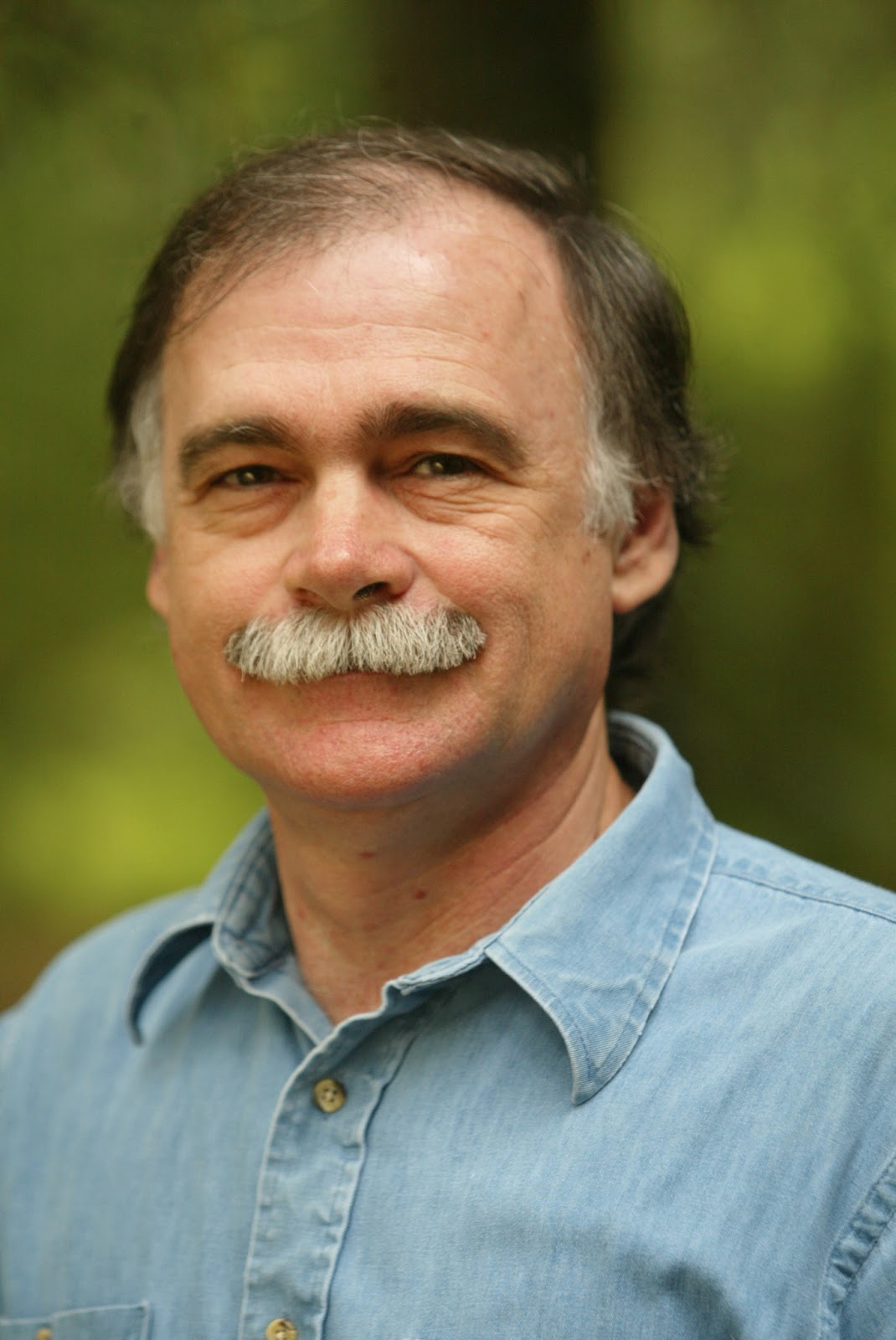

Tim Gautreaux’s career has been long and prolific, spanning three novels and two collections of short stories that have established him as one of the South’s finest writers. In his latest, Signals: New and Selected Stories, he marshals 21 new and selected stories into a sprawling collection that proves him to be a master of the form.

Tim Gautreaux’s career has been long and prolific, spanning three novels and two collections of short stories that have established him as one of the South’s finest writers. In his latest, Signals: New and Selected Stories, he marshals 21 new and selected stories into a sprawling collection that proves him to be a master of the form.

Signals is an apt title: In it, Gautreaux ranges far beyond his home turf of Louisiana’s bayous and backwoods and across the American landscape. The people of his fiction, however, remain familiar—the type of folk that one tends to see but not hear, from lonely spinsters to exterminators to house framers. Yet their sagas of wistfulness and small-time heartbreak bristle with the veracity of real life. Even when their stories are mean and brutal (“Sorry Blood” and “Gone to Water”), Gautreaux’s characters are fully fleshed enough to allow us to understand them even as we dislike them, recalling novelist Harry Crews’s maxim that “nobody is a villain in his own heart.” More often, however, the people of Signals are workaday folk trying to do their best in a world where the dogs usually bite, the beer is seldom cold enough, and the picnics tend to get rained out.

Witness the reluctant Samaritan narrator of “Deputy Sid’s Gift.” At confession for the first time in years to unburden himself of his treatment of a homeless man, he tells us that “everybody’s got something they got to talk about sometime in their life.”

And talk he does, spinning a tale of strained charity in which the spirit of compassion alternately flickers and dies. He recalls watching the homeless man “staring up into the black cloud bank, waiting for lightning. That’s how people like him live, I guess, waiting to get knocked down and wondering why it happens to them.” The passage rings out like the thematic center of Signals—stories of people watching and waiting, getting knocked down and wondering.

In “Idols”—arguably the book’s standout story—Gautreaux literally and figuratively dismantles the neoconfederate myth of vanquished glory and nobility. In it, Julian, the washed-up descendant of a Mississippi cotton baron, inherits the family’s dilapidated antebellum mansion. Returning to refurbish a legacy that never was truly his, Julian employs an African-American carpenter named Obadiah, pays him near-starvation wages, and reestablishes the old exploitative order.

By the story’s end, however, Julian’s dreams are indeed gone with the wind, but not in any way the reader will foresee. He is taught a searing lesson by a “long-suffering and moralizing carpenter” who resembles another carpenter of old. “Idols” is a finely wrought parable that deserves a place alongside the short fiction of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor.

Tim Gautreaux

Yet for all the tragedy and misfortune in the stories, there is a vein of rich humor running throughout Signals. Perhaps no other contemporary writer save Chris Offutt bears the mantle of Mark Twain as deftly. The wry, dry, ironic tone that Twain introduced to American letters is alive in Gautreaux’s fiction. His characters muddle their way through life with an air of good-natured befuddlement, from “The Bug Man” who maintains that “(h)e was a religious man, so everything had a purpose, even though he had no idea what” to the city waterworks supervisor who has “a great desire to be famous, if only in a small way” (“Radio Magic”).

Often the violence in the stories carries a bawdy frontier justice reminiscent of Old Southwestern humor, such as when the bug man hoses down an entire abusive family with bug spray or when an old man hits a young lout from behind with “a roundhouse, open-palm swat on the ear that knocked him out of the chair and sent the beer bottle pinwheeling suds across the floor.”

Yet the strongest impression that Gautreaux’s latest leaves on the reader is a love of language, a reverence for good prose, for the craft of the word. At the conclusion of one fine story Gautreaux writes: “He closed his eyes and called on the old farm in his head to stay where it was, remembered its cypress house, its flat and misty lake of sugarcane keeping the impressions of a morning wind.” Few contemporary writers can match such prose, and it runs through Signals like filigree, reminding us that into mundane lives, big drama—and beauty—can often intrude.

Novelist Matthew Guinn is the author of The Resurrectionist and The Scribe. He teaches creative writing at Belhaven University.

Tim Gautreaux will serve as a panelist on the “Historical Fiction” discussion at the Mississippi Book Festival on Saturday, August 19 at 10:45 a.m. at the State Capitol in Room 201H, and also on the “National Literary Panel” at 2:45 p.m. in the Galloway Sanctuary

With

With