By Jim Ewing

Special to The Clarion-Ledger

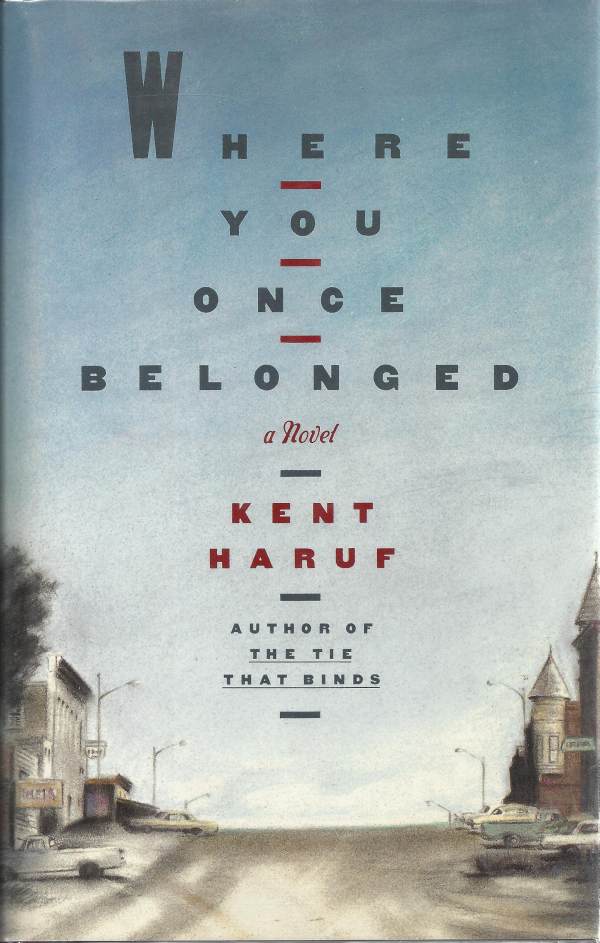

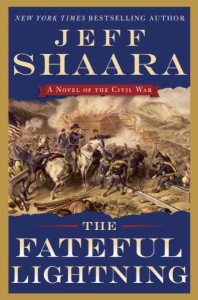

Sometimes, fiction can be more revealing of the truth than nonfiction, and in Jeff Shaara’s The Fateful Lightning: A Novel of the Civil War, the bones of nonfiction shine through his artful narrative.

Sometimes, fiction can be more revealing of the truth than nonfiction, and in Jeff Shaara’s The Fateful Lightning: A Novel of the Civil War, the bones of nonfiction shine through his artful narrative.

This 614-page saga focuses on a less studied segment of the war, Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s march to the sea and thence into the Carolinas, which is usually overshadowed by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Lightning is the fourth and final volume of Shaara’s Civil War series that previously included the battles of Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga (though it’s not necessary to have read any of the previous books to enjoy this one). It covers the campaigns from November 1864 through the end of the war in North Carolina in April 1865. For the South, Lee’s surrender was the symbolic end of the war, while Sherman’s march continued the war’s misery for generations. It set a heinous standard of “total war,” waged intentionally against civilians.

Shaara adds the insights, motivations and behavior often overlooked: breakdown of civil authority in the South; the assistance of Confederate forces in the destruction, in advance of Sherman in order to starve his army; the hatred of the civilian population of both sides of the conflict for that destruction; as well as the need for constant foraging for food by both armies, including for the freed slaves numbering 50,000 following Sherman’s 60,000-man army.

We may think of Sherman’s march as a lightning strike, as the name suggests, but it might more accurately be seen as a big, hungry hurricane consisting of four broad columns of men about 75 miles wide moving about 15 miles per day through 2,000 miles of the South.

Shaara takes pains to say that Sherman only ordered facilities of use to the enemy to be destroyed, that the actual burning of entire cities — including his worst conflagration, Atlanta — was the result of being unable to control his men.

Shaara lays bare the outlines of this segment of the war, keeping up the suspense, even as the outcome is known, by detailing Union Gen. Ulysses Grant’s concerns in the East; Sherman’s burning the heart out of the Deep South; both men fighting constant rearguard actions against politicians, the press, the duplicitous greed of those whose allegiance is to profit, no matter whose flag flies over it; and the jealous, second-guessing of subordinate generals.

Shaara’s brilliance is credibly crafting the thoughts, motivations, strategies and personalities of the leaders on both sides of the conflict. He also weaves the narrative of a slave named only Franklin, who gives the unique perspective as one of the emancipated, giving voice to those who latched on to the hope of freedom and Sherman as savior, a faith at least somewhat betrayed at Ebenezer Creek in Georgia.

There will be some grousing, for sure, from those who see Lightning as a whitewash of Sherman. It’s a point Shaara notes, saying that perhaps no more polarizing figure exists from the conflict, regarded alternately as its finest battlefield commander and ranking among the nation’s finest with George Patton and Douglas MacArthur versus a “savage,” his very name “a profanity.”

While Lightning may not be a history book, but historical fiction, students of the Civil War will find much to debate, and readers just looking for an absorbing novel will be well rewarded.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at The Clarion-Ledger, is the author of seven books including Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them, in stores now.

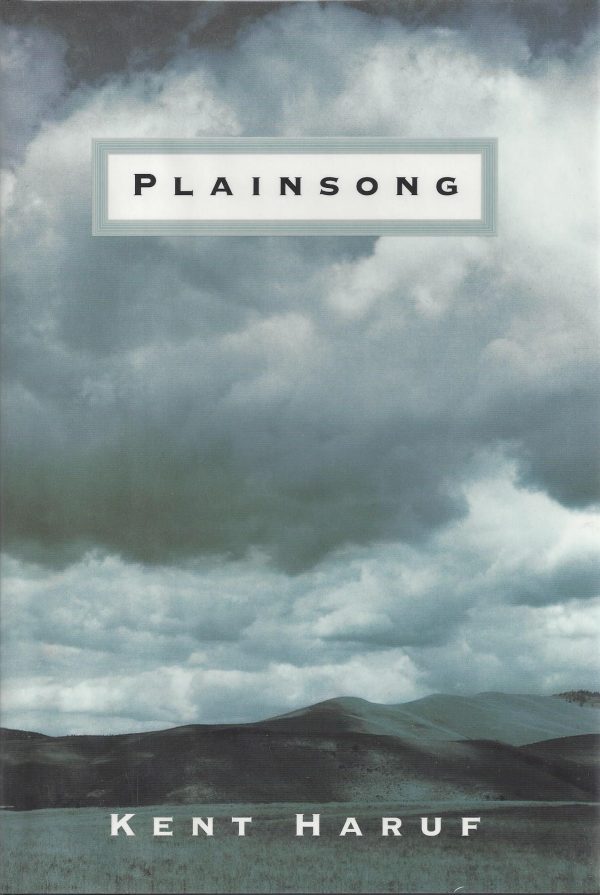

In 1998 Haruf’s agent sent “Plainsong” to Knopf, and Gary Fisketjon became his editor. Besides the intense yet never overbearing editing that Fisketjon offered, the two developed a friendship over part of Haruf’s 15-city author tour. “Plainsong” received a National Book Award nomination as well as adoration from a growing fan base. Fisketjon recalls on his blog, “

In 1998 Haruf’s agent sent “Plainsong” to Knopf, and Gary Fisketjon became his editor. Besides the intense yet never overbearing editing that Fisketjon offered, the two developed a friendship over part of Haruf’s 15-city author tour. “Plainsong” received a National Book Award nomination as well as adoration from a growing fan base. Fisketjon recalls on his blog, “