Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (August 11)

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

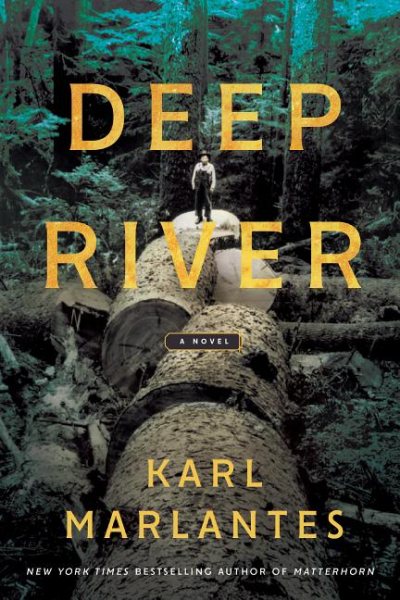

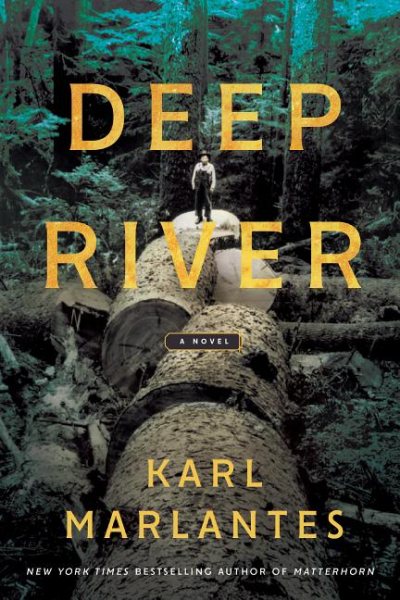

His latest case in point is his second novel, Deep River, which fills more than 700 pages as it winds its way through the tale of three sibling Finnish immigrants in early 20th century America.

His award-winning debut novel, Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War, was a New York Times bestseller that also had much to say, as Marlantes draws on his own experiences as a highly decorated U.S. Marine during that conflict; and his autobiographical What It Is Like to Go to War explores his personal impressions on war.

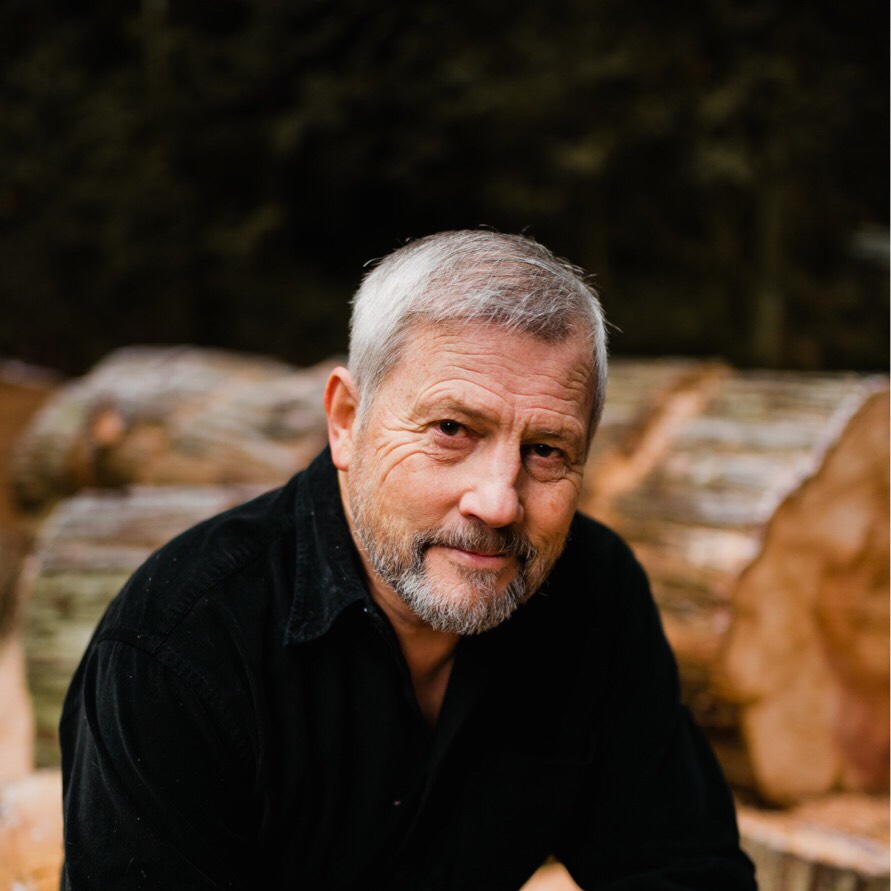

An Oregon native, Yale graduate and Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, he now lives in rural Washington.

What influenced your interest in history (in general), and the specific time and location of Deep River, set in the Pacific Northwest from 1893 to 1932?

Karl Marlantes

I’ve always loved reading history. It provides great lessons for anyone who cares to think about what has gone on before. One of the quotes in my non-fiction book, What It Is Like to Go to War, is from Otto von Bismarck: “Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.” That time period was also interesting to me because it was, in my opinion, the time of most dramatic change. My grandmother went from no electricity, no running water, horses and buggies, to freeways and landing on the moon. The question of how to adapt in a human and loving way to changing technology is still with us, and still inadequately answered.

The book chronicles the saga of two brothers and a sister who are forced to leave their farming life in Finland and migrate to a logging and fishing community in Washington state to escape the harsh Russian occupation of their homeland. The siblings come to America with differing dreams and personalities: there is Aino, the activist who was introduced to socialism at age 13 by her teacher; Ilmari, a blacksmith with dreams of church building; and Matti, the fortune-seeker. Tell us briefly about each of these characters, and their ultimate roles in the novel.

All of us adopt a stance toward life, based on such things as character, aptitude, and what happened to us as we were growing up. Kierkegaard refers to the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. These stances are how we deal with such imponderables as our own death and destiny.

Aino is an atheist–she firmly believes no one is coming to help, so we must build heaven on earth, in her case through communism and then the IWW (International Workers of the World). Her brother Matti learns early that rich people suffer much less than poor people. He is like many Americans who think we can just take out an insurance policy against mortality by driving virtually indestructible SUVs to soccer games. Ilmari is traditionally religious. There is a heaven, and we’ll all get there, but in the meanwhile, there are some serious unanswered questions, like why some children suffer and go to heaven just like the ones who don’t. He moves from traditional Christianity to an amalgam of Christianity and mysticism, which has been my own spiritual journey.

The characters are also highly influenced by their counterparts in The Kalevala. Aino who refuses marriage to an older man through suicide; Matti, hot-headed Lemminkäinen; Ilmari, the powerful blacksmith; Ilmarinen, who forged the magic sampo, the mill that grinds out eternal bounty; and Jouka, who echoes Joukahainen, the celebrated minstrel.

Explain “sisu” and its importance in the lives of the characters in Deep River.

Sisu is what won The Winter War of 1939 against the overwhelming might of the Russian army. As a child, if I fell and hurt myself and even started to whimper, my mother or grandmother would ask, “Where’s your sisu?” I would find it and not whimper. It’s courage, stubbornness, stoicism, many such traits combined and very hard to define.

In the lives of my characters, it is a major force in surviving, getting done what must be done to put food on the table, standing up against odds that any reasonable person would run from. Sisu is not reasonable. And, as Vasutäti points out, it is not always applicable.

Along with your debut book Matterhorn, you are developing a reputation for lengthy, robust narratives that fully develop your characters, their timelines and their settings–and both are packed with historical details and sweeping landscapes. Did you set out to produce epic works (that would rise so quickly to bestseller status), or did your stories just work themselves out to be generous volumes?

I swear I’ll correct that image with my next novel, but then again, stories tend to just keep happening to me while I’m writing. I never set out to write epic works. I do know, however, that among my favorite novels are War and Peace, Anna Karenina, and The Brothers Karamazov, all hefty volumes. As a reader, I like to get into a world, and if the writing is good, feel disappointed when I leave it. So, in that respect, long novels are good. I am also much taken by true epics, the “Táin Bó Cúailnge” of the Irish, the “Song of Roland” of the French, “The Iliad and Odyssey” of the ancient Greeks, “The Aeneid of the Romans,” and “The Kalevala of the Finns.”

Many reviews note that Deep River is, in part, somewhat of a comment on today’s political state in America. Could you address that?

The two major protagonists, Aksel and Aino, are almost allegorical figures for this tension in American political life between the collective and the individual. We seesaw between the two, The Great Society followed by Ronald Reagan. The Roaring Twenties followed by The New Deal.

Aksel and Aino both learn that they need each other to make it through life. It’s called compromise, something we have lost in today’s political scene. There are many parallels between the time of the novel and now, not even remotely allegorical: wars being fought that involved no immediate threat to our own security, opposition to those wars being characterized as unpatriotic, giving up individual privacy and freedom to the Espionage Act of 1917, which was sold to protect us from “bolshevism” and used to crush the IWW in the name of national security, and the Patriot Act of today, which was sold to protect us from terrorists and justified by the same reasoning, horrible income inequality, the struggle to make a living wage, the unconscious destruction of our natural environment, the problems associated with immigration, false stories in biased newspapers, all compounded by a feckless federal government.

Karl Marlantes will be at the Lemuria on Wednesday, August 14, at 5:00 to sign and read from Deep River. Lemuria has selected Deep River as its August 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

* * *

Marlantes will also appear at the Mississippi Book Festival August 17 in coversation with Tom Franklin and Kevin Powers at 12:00 p.m. at State Capitol Room 113.

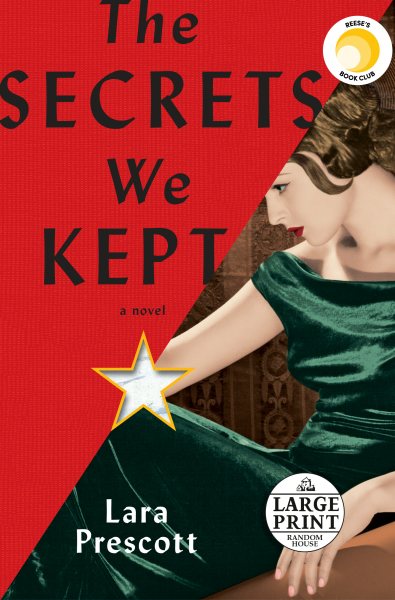

The Secrets We Kept is a debut novel by Lara Prescott based on the true events surrounding the 1957 publication of Dr. Zhivago, a 20th century literary masterpiece combining a sweeping love story with intrigue, political hardship, and tragedy, set between the Russian Revolution and WWII. One of the greatest love stories ever written, it was made into the haunting film featuring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif. Boris Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for it, which he was made to turn down by an embarrassed and outraged KGB. It was banned reading there until 1988. But if you haven’t read it, now you’re up to speed, and you can read The Secrets We Kept!

The Secrets We Kept is a debut novel by Lara Prescott based on the true events surrounding the 1957 publication of Dr. Zhivago, a 20th century literary masterpiece combining a sweeping love story with intrigue, political hardship, and tragedy, set between the Russian Revolution and WWII. One of the greatest love stories ever written, it was made into the haunting film featuring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif. Boris Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for it, which he was made to turn down by an embarrassed and outraged KGB. It was banned reading there until 1988. But if you haven’t read it, now you’re up to speed, and you can read The Secrets We Kept!

If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s

If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s  A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.

A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.

Téa Obreht’s sophomore novel

Téa Obreht’s sophomore novel

Hosted by each site’s Friends of the Library, a non-profit advocacy group aimed at supporting public libraries through fundraising and promotion, Adele adapts her program to the group and, depending on their interests, discusses either her novel, which deals with a sexually abused graffiti artist, or her memoir, which details her experiences with her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s.

Hosted by each site’s Friends of the Library, a non-profit advocacy group aimed at supporting public libraries through fundraising and promotion, Adele adapts her program to the group and, depending on their interests, discusses either her novel, which deals with a sexually abused graffiti artist, or her memoir, which details her experiences with her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s. Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

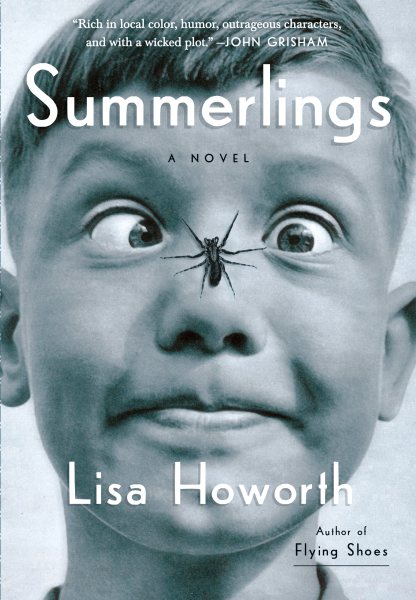

Oxford’s Lisa Howorth combines a humorous twist with the looming realities of an America on the cusp of the 1960s in her sophomore novel,

Oxford’s Lisa Howorth combines a humorous twist with the looming realities of an America on the cusp of the 1960s in her sophomore novel,

When I began reading about Stella Fortuna, I had no idea I would be swept up on an encompassing journey with such an incredible woman. This debut novel from Juliet Grames, whose full title is

When I began reading about Stella Fortuna, I had no idea I would be swept up on an encompassing journey with such an incredible woman. This debut novel from Juliet Grames, whose full title is