I love animals. All of them. The cute ones, the dangerous ones, the ones that sleep in our houses, and the ones that hide in remote rainforests, only ever exposing themselves to a few, lucky sets of human eyes.

I’m guessing you probably love animals too. Maybe you have a couple of dogs, cats, or goldfish at home; or maybe you take your nieces and nephews to the zoo when they’re in town; or maybe your computer wallpaper features a sleepy-eyed koala front and center (mine is a snow leopard). Regardless of how it manifests itself, a love for animals is shared by three out of every four Americans.

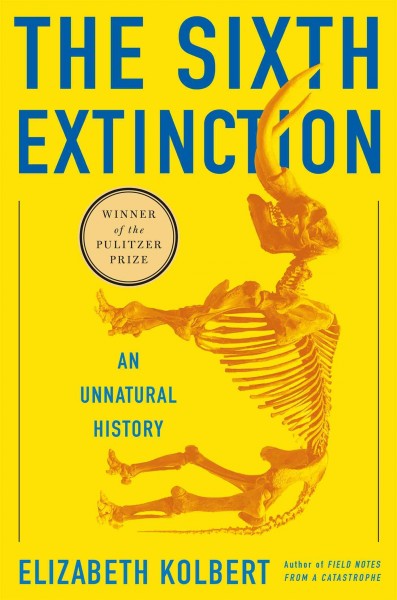

Well, guess what… They’re all dying… or at least a lot them are. So says Elizabeth Kolbert in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Sixth Extinction.

Well, guess what… They’re all dying… or at least a lot them are. So says Elizabeth Kolbert in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Sixth Extinction.

Kolbert, author of the acclaimed Field Notes from a Catastrophe and a staff writer at the New Yorker since 1999, spent several years traveling the globe learning from scientists in various fields who study the changing environment and its effects on Earth’s animal and plant life. Her conclusion? By the end of the century, 20 to 50 percent of all species will be extinct.

The first several chapters of the book cover the five mass extinctions chronicled in the fossil record, including the most recent extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. From mollusks to mastodons, Kolbert handles the dearly departed species with delicacy, and presents the science behind their disappearance in a way that is easily digested for the layperson. She also describes the gradual acceptance of mass extinctions among scientists of the 18th and 19th centuries led by the likes of Cuvier and Darwin. The idea that an individual species could disappear from the earth entirely was hard to imagine only three hundred years ago. The idea that a force could eliminate species en masse was totally unthinkable.

Jumping to the present, Kolbert travels from Central America, where beloved frog species have disappeared in a matter of years, to the coast of Australia, where coral reefs home to thousands of species are receding due to increased ocean acidification. She introduces the idea that we are living in a new epoch called the Anthropocene in which human activity has become the dominant factor impacting the natural world. Since the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, scientists estimate that around one to five species went extinct each year. Fast-forward to the Anthropocene, and the rate is now more than a dozen species each day!

In one of the most memorable anecdotes of the book, Kolbert explains the arrival of the brown tree snake on the island of Guam via military ships in the 1940s. Devoid of any natural predators, the snake “ate its way through most of the islands native birds” lacking any natural defense from the foreign predator and reduced the island to one native species of mammal. “While it’s easy to demonize the brown tree snake, the animal is not evil; it’s just amoral and in the wrong place,” says Kolbert. It has done “precisely what Homo sapiens has done all over the planet: succeeded extravagantly at the expense of other species.”

For such grim content, the book remains surprisingly upbeat. From chapters entitled “Dropping Acid” to a detailed scene of a zookeeper sticking a gloved hand up the rectum of a rhino, Kolbert does her best to maintain a sense of humor throughout. Most importantly, she ends on an optimistic note, focusing on the successful efforts that can and are being done to save species. “People have to have hope. I have to have hope. It’s what keeps us going.”

Here’s to hoping that the koala on your screen will be around for generations to come.

Comments are closed.