Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 24)

Award-winning children’s book author and illustrator Philip Stead has the unique honor of being the only person alive today who can claim the title of “co-author” to a Mark Twain tale.

LIke most things associated with Twain, who died in 1910, the story of how that came about is, well, an interesting story.

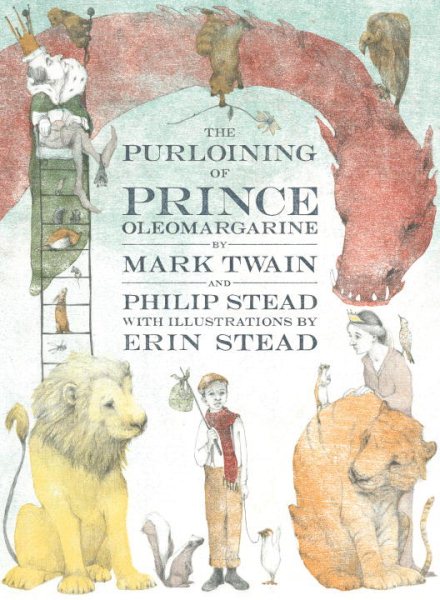

But first things first. Before his collaboration with Twain on the newly released The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine, Stead and his artist wife Erin Stead claimed a Caldecott Medal, along with the titles of New York Times Best Illustrated Book of 2010 and a Publishers Weekly Best Children’s Book of 2010, for their book A Sick Day for Amos McGee.

Together the couple also created Bear Has a Story to Tell, an E.B. White Read-Aloud Award honor book and, among others, Lenny and Lucy. As an artist as well as author himself, Stead has written and illustrated several books, including his debut, Creamed Tuna Fish and Peas on Toast.

The husband and wife team met in a high school art class, “and from the very first days, we planned on making books together,” Stead said.

Today, they live and work in northern Michigan, along with their dog, Wednesday, and their 5-month-old daughter, Adelaide.

How did the idea for this book come to be–it’s quite unusual!

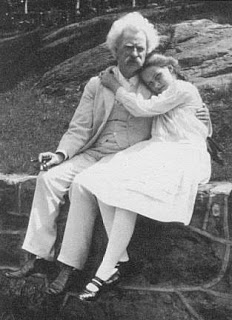

The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine began as a story told by Mark Twain to his tow young daughters in the year 1879. Twain probably told countless stories to his children, but this is presumed to be the only time he committed notes for one of these stories to paper.

In 2011, the notes were discovered at the Mark Twain Archive in Berkeley, California. They were unearthed by a scholar who was doing research for a Mark Twain cookbook. He opened a folder labeled “Oleomargarine” expecting to find something food-related and instead discovered 16 pages of handwritten notes for a children’s story begun but never finished. Eureka!

How was it that you were chosen to write this book?

Honestly, I wish I knew! Probably there were others before us who were smart enough to say, “thanks, but no thanks.” But seriously, my best guess is that Erin’s artwork gave our editor confidence that maybe we could do this. Erin’s work is often described as old-fashioned. In an increasingly digital world, Erin has stuck with traditional techniques like woodblock printing and pencil drawing, both of which were around in Twain’s day. One challenge with this book was how to bridge the divide from 1879 to 2017. I think Erin’s art style helps bridge that gap.

Please give me a brief description of the story line, including the main characters. (Your technique of serving as the narrator for your own story, and holding conversations with Mark Twain, was great!)

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken.

Johnny, a poor, kind, young boy, is forced one day by his cruel grandfather to sell his pet chicken at the market. In doing so, he unexpectedly comes into possession of some magical seeds. From the seeds grow a flower, and upon eating the flower, Johnny is granted the ability to speak with animals. Led by a skunk named Susy, Johnny and all the animals in the land set out on a quest to rescue a stolen prince, and with some luck, perhaps cross paths with a familiar chicken.

Generally, where did Twain’s notes on this book end, and where did you take up the story?

Twain’s notes end at the mouth of a dark cave where, presumably, Prince Oleomargarine is being held by giants. Twain’s final words are: “It is guarded by two mighty dragons who never sleep.” So, Twain was very close to an ending already.

What we discovered was that the ending was not really the missing piece. The missing piece was the beginning. Twain’s notes begin abruptly with: “Widow, dying, gives seeds to Johnny–got them from an old woman once to whom she had been kind.” That’s certainly a nice place to begin, but Twain left us with nothing about the character of Johnny–who he was and why we ought to love him.

Some characters in the book were created by Erin and me to address this problem. The most notable additions are probably the cruel grandfather and Johnny’s luckless pet chicken, Pestilence and Famine. The name Pestilence and Famine, by the way, comes from a piece of Clemens family history. The Clemens family had many household cats with peculiar names. There was a cat named Sour Mash, and Satan, and my personal favorite, Pestilence and Famine.

What inspired the direction you decided to take in finishing this tale?

The book became a story within a story. First, there is the story of Johnny, and Susy, and Prince Oleomargarine. But then there is the story of Mark Twain and myself, sitting together at a secluded cabin, arguing over the direction of the story itself. These conversations between Twain and me came about because of a problem I encountered early on. The problem was that every now and then I wanted to deviate from Twain’s notes. It didn’t seem right, though, to make changes without giving Twain a say in the matter. The easiest and most fun solution to this problem was to make Twain (and myself) a character in the book.

Tell me about the artwork Erin produced for this book. How does it help to convey your own “vision” for this story?

Erin’s artwork is rendered in woodblock printing and pencil drawing. The colors are muted and atmospheric. In many ways, Erin became a third author for this story. So many choices were left completely up to her. It was never just a matter of executing my, or Twain’s, vision.

For example, the setting is all Erin’s. Oleomargarine is a fairy tale, but it is not a European fairy tale. It is American through and through. Erin wanted the setting to reflect that. She also wanted the setting to exist somewhere in time between Twain’s day and our own. So, having given herself those two guidelines, she settled on a world reminiscent of the American dust bowl–a perfect setting for her naturally dusty, airy, and melancholy artwork.

For what ages is this book most appropriate?

This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life.

This story began as a piece of oral tradition. It was as a story told out loud, maybe over the course of several nights by an adult to children. I would hope the finished book is used in much the same way. While the language might be difficult for a child under the age of 9 or 10, I believe that children of all ages will be able to appreciate the story–its rhythm, its humor, and its message–especially when told directly to them by a parent, or grandparent, or some other important adult figure in their life.

In what ways did you find it most challenging to complete the task of finishing Twain’s story, and on the flip side, what did you enjoy most about tackling this project?

The most challenging thing about this book was also the most rewarding. For me, the real work and the real joy was in finding Twain’s voice. Twain left notes for almost every element of plot, but he left very little finished prose. Because of that, I had to really immerse myself in Twain’s other works, sometimes listening to Twain’s writing as if it were music. Because of that, there is a little bit of Twain inside of me now forever.

Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

Paul Lacoste has spent his career coaching others into top physical form, and he’ll be the first to admit that when it comes to getting his clients in shape, he’s not known for taking a subtle approach.

In

In

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book  What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades?

You’ve enjoyed a full life — world traveler, family man, would-be farm hand and at times you’ve turned your attention to politics (mostly through your deep interest in policy), journalism, the military, and your own formal education, not to mention an amazing career as a writer. How have you managed to fit so many interests into your seven decades? Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?

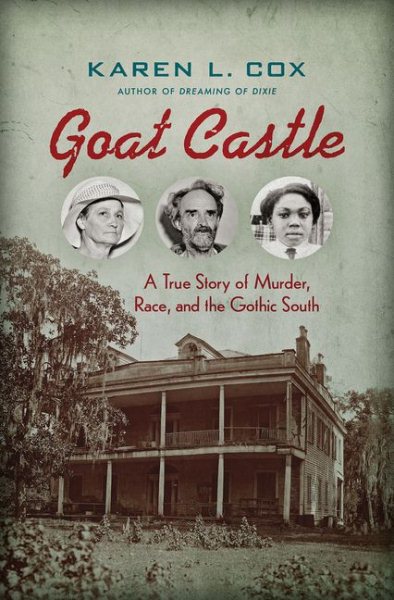

Your newest book, “Paris in the Present Tense,” is another fictional work presented on a grand scale. In this story of an aging man consumed with worry about his grandson’s serious illness, main character Jules Lacour is keenly aware of his own inability to offer much in the way of financial support. A deep thinker with strong convictions, he looks back on his own life with his share of regrets and fears. In many ways, most of us have a lot in common with Lacour. Can you share your reflections on him?  Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time.

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time. Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,