By Susan Cushman. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (January 12)

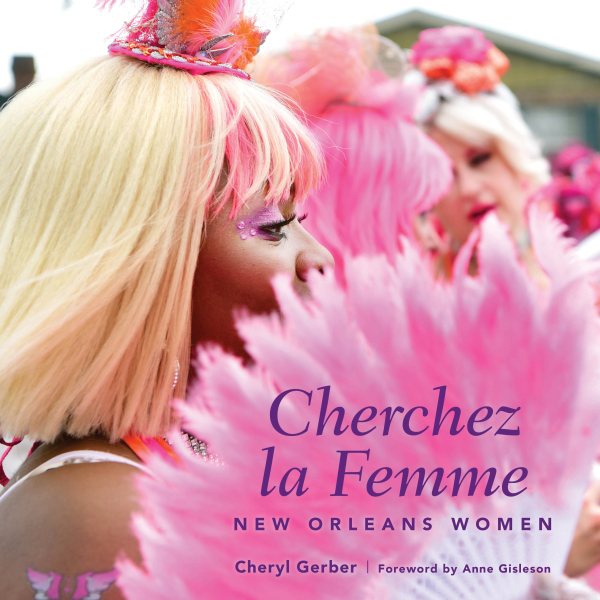

Inspired by the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., New Orleans native and documentary photographer Cheryl Gerber has, in her new book Cherchez la Femme: New Orleans Women, curated an incredible collection of over 200 color photographs and 12 essays, showcasing both famous and lesser-known New Orleans women. Gerber set out to show their “grit and grace” and their “beauty and desire,” and I believe she succeeded in a big way with this gorgeous large format hardcover masterpiece.

Inspired by the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., New Orleans native and documentary photographer Cheryl Gerber has, in her new book Cherchez la Femme: New Orleans Women, curated an incredible collection of over 200 color photographs and 12 essays, showcasing both famous and lesser-known New Orleans women. Gerber set out to show their “grit and grace” and their “beauty and desire,” and I believe she succeeded in a big way with this gorgeous large format hardcover masterpiece.

Cherchez la femme literally translates as “look for the woman.” In his 1854 novel The Mohicans of Paris, Alexandre Dumas repeats the phrase several times. Since then the French have often used it in a sexist manner, implying that women–or “the woman”–must be the cause of whatever problem is being described. It brings to mind Adam’s reply to God’s question concerning his transgression with the forbidden fruit; he blamed it on “the woman you gave me.”

In her homage to those women, Gerber has turned that phrase on its head, inviting the reader to look for the women who have made and are still making significant contributions to their colorful city.

My use of the word “colorful” is intentional. In the foreword, New Orleans native Anne Gisleson prepares us for the tour de force that Cherchez la Femme is–a tribute to the monumental achievements of colorful women and women of color.

Beginning with the Ursuline nuns and their beloved Lady of Prompt Succor who ran the hosptials and schools for people of all races as early as the War of 1812, and later as French baroness Macaela Pontalba fought to protect and rebuild the historic architecture of her beloved city. Gisleson introduces us to Henriette Delille–a free woman of color who started her won order to feed and educate the poor, since she wasn’t allowed to join the Ursulines.

Gerber’s loving tribute to chef Leah Chase (1923-2019) and Helen Freund’s essay about Chase in the culinary chapter set a celebratory tone for the stories that follow. Gerber organized these into topical chapters: Musicians, Business, Philanthropists and Socialites, Spiritual, Activists, Mardi Gras Indian Queens, Mardi Gras Krewes, Baby Dolls, Social and Pleasure Clubs, and Burlesque. The contributors include publishers, authors, historians, journalists, and educators.

Fifty years ago, the New Orleans-born gospel great Mahalia Jackson debuted at Jazz Fest. In her essay, Alison Fensterstock hails Jackson as “an artist whose powerful creative spark and spiritual passion shaped the sound not only of the city, but also of her nation.”

In her essay, Kathy Finn says that female entrepreneurs–including Voodoo practitioners, strippers, clothing and jewelry designers, and professional sports team owners–are “helping to ensure that the city” retains its unique character far into the future.”

Sue Strachan tells us about a bevy of female philanthropists, lobbyists, social columnists, and fundraisers who have “a passion for making the community a better place.”

The city of New Orleans–named for a young French girl who saw angels and saints and led France in a victory over England, “The Maid of Orleans,”–today “serves as the cauldron where these archetypal forms simmer together: the saints, the nuns, the witches, the mambo…a distinctively feminine spirituality…that runs through the streets…” Constance Adler found her true home there through a Voodoo priestess’ “gestures, words, and smoke at the altar.”

Katy Reckdahl shines a light on many women activists, showing us that “the tradition of resistance in New Orleans is particularly strong.”

Mardi Gras Indian Queens like essay contributor Charice Harrison-Nelson, also known as Maroon Queen Reesie, is one of 16 Indian Queens Gerber photographed for the book. Did I mention this city (and the book) is colorful?

While Krewes were male-dominted in the past, women have become “the architects of a new carnival experience,” as Karen Trahan Leathem explains in her essay.

Kim Vaz-Deville goes into more depth about the Baby Dolls, offering an opportunity for black women who were previously shout out of Mardi Gras. Gerber captures 14 of these dance groups in her amazing photographs.

Social and pleasure clubs keep the tradition of second-line parades alive. Karen Celestan explains in her essay: “The kinetic procession viewed on weekend streets in the Crescent City is nothing less than liquid muscle memory….It is fresh joyfulness, majestic, paying tribute to their ancestors.”

Gerber’s final chapter features an essay by Melanie Warner Spencer, who writes about the resurgence of burlesque. Today’s stars–like Bella Blue, Louisiana native and mother of two–are often trained in classic ballet. Blue is also headmistress of the New Orleans School of Burlesque. Spencer says burlesque “promotes a message of fun, fabulousness, confidence, and body positivity…keeping alive an art farm that is as much a part of the history of New Orleans as streetcars and beignets albeit a dash naughtier.”

“Fun and fabulousness” are also words I would use to describe Cherchez la Femme, a beautiful love letter to the women of New Orleans.

Jackson native Susan Cushman is editor of Southern Writers on Writing and two other anthologies. She is author of short story collection Friends of the Library, the novel Cherry Bomb, and the memoir Tangles and Plaques: A Mother and Daughter Face Alzheimer’s.

Mississippians are especially fortunate in that we likely have more independent bookstores per capita than any other state in the union.

Mississippians are especially fortunate in that we likely have more independent bookstores per capita than any other state in the union. New York Times bestselling author Susannah Cahalan shines a light on a turning point in the field of psychology with her second book,

New York Times bestselling author Susannah Cahalan shines a light on a turning point in the field of psychology with her second book,

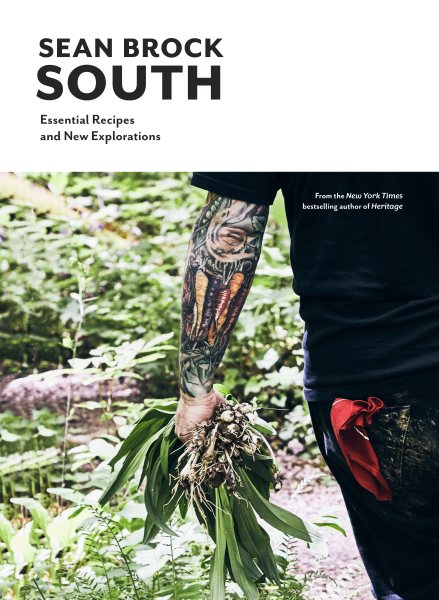

Sean Brock, award-winning chef at the iconic Charleston, South Carolina, restaurant Husk, seems to find himself at a turning point. Like many Southerners, he is deeply aware of the concept and complexities of place.

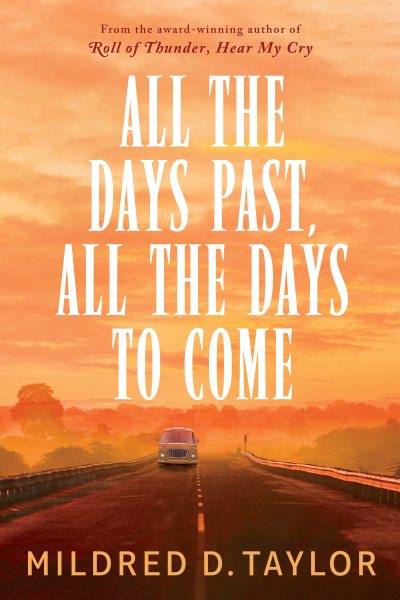

Sean Brock, award-winning chef at the iconic Charleston, South Carolina, restaurant Husk, seems to find himself at a turning point. Like many Southerners, he is deeply aware of the concept and complexities of place. Mildred Taylor wraps up her 10-book series that has followed the lives of the Logan family from slavery to the Civil rights movement with her final addition,

Mildred Taylor wraps up her 10-book series that has followed the lives of the Logan family from slavery to the Civil rights movement with her final addition,

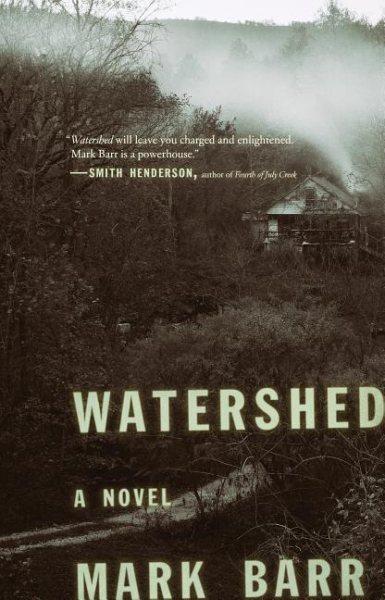

Mark Barr’s debut novel

Mark Barr’s debut novel  New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett’s seventh novel

New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett’s seventh novel

Award-winning New York Times bestselling author Karen Abbott adds to her popular lineup of historical nonfiction with

Award-winning New York Times bestselling author Karen Abbott adds to her popular lineup of historical nonfiction with

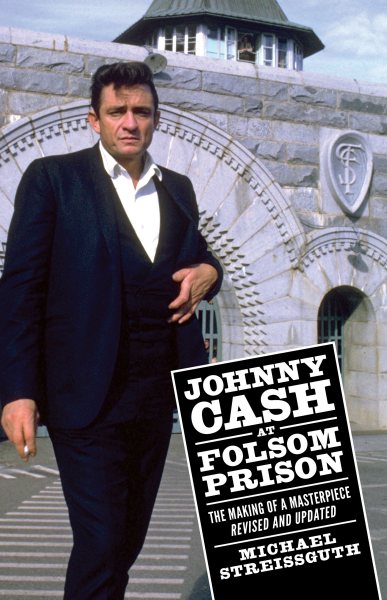

The morning of January 13th, 1968, Johnny Cash rode half an hour from Sacramento to the granite walls of Folsom State Prison. With Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers as openers, he played two shows at 9:40am and 12:40pm. The composite recording of the proceedings would surpass 3 million units sold.

The morning of January 13th, 1968, Johnny Cash rode half an hour from Sacramento to the granite walls of Folsom State Prison. With Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers as openers, he played two shows at 9:40am and 12:40pm. The composite recording of the proceedings would surpass 3 million units sold. Fans of the late Oxford author Larry Brown need wait no longer to own a collection of his career short works in one volume, with the release of Algonquin’s

Fans of the late Oxford author Larry Brown need wait no longer to own a collection of his career short works in one volume, with the release of Algonquin’s