Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print and online editions (April 8)

When Francisco Cantú decided to join the U.S. Border Patrol as a new college graduate in 2008, he expected the work to be tough, but after four years, the realities of the job forced him to examine the morality of his duties–and a gut check told him clearly: “It’s not the work for me.”

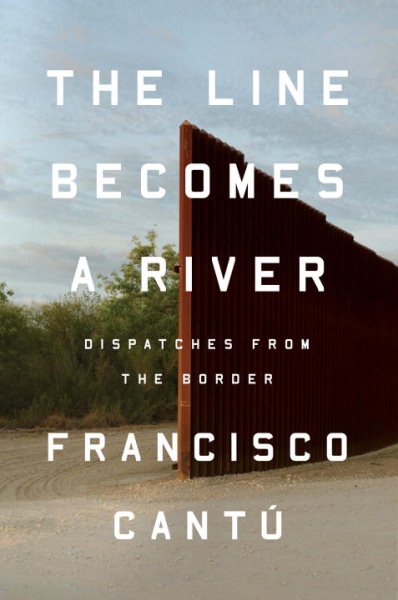

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol, The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border (Riverhead Books), Cantú recounts the physical and emotional toll the experience took on him, and his growing angst about what really happens in the desert to those who attempt to cross.

In a memoir about his duties with the patrol, The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border (Riverhead Books), Cantú recounts the physical and emotional toll the experience took on him, and his growing angst about what really happens in the desert to those who attempt to cross.

Written in three parts, the book describes his training and introduction to the brutal field work; his transfer to a desk job in the intelligence division; and his personal involvement in the case of an undocumented friend who got caught up in the legalities of crossing the border.

A former Fulbright fellow, Cantú was a recipient of a Whiting Award for emerging writers in 2017. His work has been featured on the This American Life radio/podcast and in Best American Essays, Harper’s, Guernica, Orion, and n + 1.

He received his MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Arizona. When he’s not writing, Cantú coordinates a research fellowship that connects MFA students with advocacy groups active in environment and social justice issues in the borderlands; teaches at the University Poetry Center; and tends bar.

When you decided to pursue a career as a U.S. Border Patrol, you knew it would be a tough job–that you would be “fetching dead bodies from the desert” in 115-degree heat, and you were cautioned by one of your early trainers: “You will be tested.” What inspired you to seek employment as a border patrol agent?

Francisco Cantú

When I first began to consider signing up for the Border Patrol, I was 22, about to graduate from college. I had become completely obsessed with the border during my studies in international relations, but began to feel that much of the book learning and policy work I had been doing was disconnected from the realities of the landscape and culture that I had known growing up. At the time, the border patrol began to seem like one of the only ways to really be out on the border day in and day out, to see the hard realities of the place.

I joined hoping to be a “force for good” within the agency, imagining I might spend several years in the patrol and then become a policy maker or immigration lawyer equipped with insights that had eluded everyone else. I knew I’d see awful things, but I imagined that I’d be able to just be an observer, not a participant, that my sense of morals and ethics would withstand the numbing forces of the institution. It was incredibly naïve.

Understandably, when your Mexican-American mother heard of your plans to work as a border patrol agent, she feared for you life and your psyche, worried that it would change you in hard ways. Throughout the book, there are episodes of her offering advice and reflections about your work. Looking back, do you see some wisdom in her words now that you didn’t see then?

From the very beginning, my mother sensed the risk I was running of becoming lost. She had spent her career working for the federal government and warned me how it is impossible to step into an institution without it repurposing your energy towards its own ends. I wish I’d listened to her more–like many young adults I thought of myself as infallible.

My mother was the only person in my life that was still holding me accountable, reminding me of the reasons I had given for joining. She was one of the only tethers connecting me to who I was outside of the job. I don’t know if I would have come out of it in the same way without her.

Your book is filled with references to frequent disturbing dreams that haunted your nights. You also suffered from teeth grinding and lack of sleep during your stint as an agent. What did you make of these episodes?

At the time, I pushed them away. But looking back on it, these dreams were the only thing in my life, other than my mother, reaching out to tell me that something was wrong, that I was not alright. It’s alarming to think of how plainly violence and dehumanization was manifest in my dreams and how it correlated with becoming numb to it through my work. I would dream, for example, of dead bodies, of people I had arrested returning to me. I once dreamed that I was in the desert surrounded by people without faces. The longer I ignored the dreams, the more jarring they became. I realize now my nightmares were alarm bells, calling me back to my sense of humanity, calling my attention to something that had been violated.

Your days as an agent were filled with encounters with immigrants headed north, determined to enter the U.S. at almost any cost. Some were drug dealers or worse, but most were just looking for honest work. You admit there were times you would work with desperate people at points along the way, often in miserable circumstances, and you would soon forget their names. Did you feel like you became desensitized to the violence and despair of many of these people?

Absolutely. The normalization of violence is a central theme of this book. That moment you mention, when I realized I had forgotten the names of a pregnant woman and her husband that I’d arrested only hours before, is one of those moments I think of all the time, because I think that’s the first step in dehumanizing someone–forgetting their name, the thing that makes them an individual. It’s a small form of violence, and, looking at that–all the big and small ways we become desensitized to violence and despair–that was one of the principal things that led me to write after I left the job.

It felt like one of the only ways to truly grapple with what I’d been part of. I became interested not only in interrogating the ways I had normalized violence in my own life, but in examining how this also happens on a much broader level, how entire societies and populations normalize violence, especially in the borderlands.

The book includes a great deal of the history of the border situation, along with reflective pieces by other writers whose point of view you deemed relevant. How did you choose these pieces, and why did you add them?

Early drafts of the manuscript included some history of the border, but I was actually given permission by my editor to include even more outside research, to really look at how this border came to be what it is. That was exciting to me–it opened the door for me to include different kinds of work that had influenced my thinking about this place: writing from Mexican poet Sara Uribe, novelist and essayist Cristina Rivera Garza, as well as citations from primary documents like the U.S. Boundary Commission Reports from the 1800s.

The purpose of including such a wide spectrum of research was to encourage an interrogation of borders: most people who don’t live near one would probably tend to think of the border as a political or physical line separating two countries. But part of living in the borderlands is being constantly presented with different manifestations of the border and seeing all the different ways it is thrust into people’s lives.

Why did you ultimately quit your job as a border patrol agent?

I accepted a Fulbright Fellowship to study abroad. There were several reasons I applied for it, and one of them, I’m sure, was to subconsciously provide myself with a way out of the job that didn’t represent a defeat, that represented a path ahead. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see that I had finally started to break down.

Once I left the Border Patrol, I realized that I didn’t get any of the answers I had joined looking for–I only came away with more questions, and the border only seemed more overwhelming and incomprehensible. My turn toward writing was a way of accepting that, of surrendering to the act of asking questions that might not have an answer.

The final third of the book is devoted to the story of José, a friend you met after your border patrol years who became trapped in Mexico after returning to his native home to visit his dying mother. José comments at length about the difficulties of trying to cross the border to return to his family, and he places much blame on the Mexican government for its corruption and lack of aid and support for its own people; while chastising America for its seeming inhumanity in attempting to turn them away. Do you have a sense of what could or should be done to resolve, or at least ease, the crisis?

I remember José explaining to me that as a father there is literally nothing that he wouldn’t endure to reunite with his children. It’s hard to really grasp the significance of somebody saying, “It doesn’t matter how hellacious an obstacle is, I will overcome it to be with my family.”

José explained to me that he respects the laws of the U.S., but his family values supersede those laws. Our rhetoric encourages us to think of people like José as criminals, but under those terms, it’s impossible for me to look at his actions as criminal. I think most of us would do the same in his situation.

I think we have to end the de facto policy of “enforcement through deterrence,” which is something you don’t hear our policy makers talk about in any of their discussions about immigration reform. By heavily enforcing the easy-to-cross portions of the border near towns and cities, we’ve been pushing migrants to cross int he most remote and deadly parts of the desert, weaponizing the landscape.

Hundreds of deaths occur there each year, and those are just the ones that get reported. Around 6,000 and 7,000 migrants have lost their lives since the year 2000. Even last year, the administration bragged that crossings were down to their lowest level in more than 14 years, but what you didn’t hear is that migrant deaths actually went up from the year before, not down. So even though less people are crossing the border, the crossing is becoming more deadly.

I see this as a complete humanitarian crisis taking place on American soil, and I don’t see our country acknowledging these deaths in the way we should. We don’t read their names, we don’t memorialize them, we don’t mourn their deaths. That’s unacceptable. We have to understand these numbers, first and foremost, as representing individual people, individual lives.

Francisco Cantú will be at Lemuria tonight, Monday, April 9, at 5:00 to sign and read from The Line Becomes a River. This book is a 2018 selection for our First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

Comments are closed.