Hey y’all, I’m Jack, a bookseller at Lemuria Books! Here at the store, we’re working hard behind the scenes to help our community stay reading by processing web and phone orders, and by using the internet and social media as tools to help you find the great books you deserve. It’s a difficult and trying time in our world, and self-quarantining and social distancing have not been easy, but at Lemuria, we’re doing what we can to make the most of this time by reading and recommending fantastic books. It’s also been a challenging time to be a passionate bookseller; 2020 has provided so many incredible books, and at Lemuria we believe in the value of face-to-face bookselling and the experience of real books, but in the meantime we are closed for browsing. Thus, we have worked tirelessly to adapt to these times by increasing our web and social media presence and by utilizing those platforms to help you find great books. In our newsletter, we have been featuring books from different sections in our store, handpicked by our wonderful booksellers, and we’d love to help you find great books from Lemuria with staff-specific favorites, as well. So, to kick things off, I’ve included some of my favorite Fiction Picks from 2020 so far, with small blurbs attached. You Deserve a Good Book, and We’d Love to Help! Thank you for supporting our store and community by keeping Lemuria alive and well during these crazy times!

Apeirogon

Fortunately, before we closed our doors to the public, we hosted an outstanding event with Colum McCann for his new novel Apeirogon. Spending time with McCann, Lemurians, and our awesome reading community that night was one of the highlights of my time here at the store. McCann and Katy Simpson Smith hosted a really awesome conversation about the book and about fiction as a way to reach a more distinct truth in our society today. It was inspiring, fun and important to the store and to our readers. I’m really grateful to have been a part of it.

Fortunately, before we closed our doors to the public, we hosted an outstanding event with Colum McCann for his new novel Apeirogon. Spending time with McCann, Lemurians, and our awesome reading community that night was one of the highlights of my time here at the store. McCann and Katy Simpson Smith hosted a really awesome conversation about the book and about fiction as a way to reach a more distinct truth in our society today. It was inspiring, fun and important to the store and to our readers. I’m really grateful to have been a part of it.

Apeirogon is a very powerful book centered around two fathers on either side of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict who connect through their mutual grief over the loss of their daughters to meaningless war terrorism incidents. Told through 1001 cantos, McCann’s novel dissects the complexities of the conflict between two nations and peoples by utilizing an innovative and highly appropriate form. These vignettes blend and disorient, contribute and connect to one another, and the overall result is nothing short of a masterpiece. This novel made me feel loved, taken into consideration as a reader, and showed me the side of fiction that makes me want to read and sell books forever: fiction that grips the heart of experiential and emotional truth. Reading this novel affected me deeply, and that experience was reinforced by McCann’s authentic and curious persona when he came to visit Lemuria. I’ll always remember it.

Verge is a clever, abrasive collection of stories by Lidia Yuknavitch, an author whose ingenuity and mastery of the short story form should be celebrated. Yuknavitch’s insightful representation of life as a woman in today’s America is conveyed in each of these appropriately brutal fictions. Her commentary on consumerism, addiction, sex and making mistakes as part of one’s path toward some sort of fully-developed identity gives the reader a sense of forgiveness and self-love. This book is really fantastic, and I’m so happy I was afforded the opportunity to read it when I read it; this is the kind of book that finds you at the right time.

Verge is a clever, abrasive collection of stories by Lidia Yuknavitch, an author whose ingenuity and mastery of the short story form should be celebrated. Yuknavitch’s insightful representation of life as a woman in today’s America is conveyed in each of these appropriately brutal fictions. Her commentary on consumerism, addiction, sex and making mistakes as part of one’s path toward some sort of fully-developed identity gives the reader a sense of forgiveness and self-love. This book is really fantastic, and I’m so happy I was afforded the opportunity to read it when I read it; this is the kind of book that finds you at the right time.

Lily King’s novel is important for 2020. Writers and Lovers tells the story of a struggling young woman, Casey Peabody, seeking to establish her identity, place and voice in both the book industry and in America in the midst of grieving the loss of her mother. Partly autobiographical, King’s novel gives an enlightening account of what it means to still be struggling into adulthood as a lone, independent woman in a man’s industry and world. Peabody champions her own disheveled path toward truth and identity in writing and loving, holding steadfast to the deeper dreams she has harbored her whole life, even when it is much easier to let those fall away and fold into an easier way of life. This book has a really universal quality that I haven’t felt from something in a while, and I think Lily King’s voice is invaluable to American fiction today.

Lily King’s novel is important for 2020. Writers and Lovers tells the story of a struggling young woman, Casey Peabody, seeking to establish her identity, place and voice in both the book industry and in America in the midst of grieving the loss of her mother. Partly autobiographical, King’s novel gives an enlightening account of what it means to still be struggling into adulthood as a lone, independent woman in a man’s industry and world. Peabody champions her own disheveled path toward truth and identity in writing and loving, holding steadfast to the deeper dreams she has harbored her whole life, even when it is much easier to let those fall away and fold into an easier way of life. This book has a really universal quality that I haven’t felt from something in a while, and I think Lily King’s voice is invaluable to American fiction today.

Like Flies From Afar is Argentinian author K. Ferrari’s brutally honest and expletive-ridden murder mystery, translated and published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux in 2020. FSG is an imprint I’ve been tuned to in the recent past, and I have yet to be disappointed by anything of theirs that I’ve taken a chance on, this novel no exception. Like Flies From Afar follows Luis Machi, a delusional Argentinian oligarch fueled by machismo and his cocaine habit, through a downward spiral of paranoia that threatens to dissolve his guise of masculinity. When Machi finds the dead body of an unidentifiable man in the trunk of his spotless BMW, he is forced to confront the realities of the dirty and drug-driven life and identity he has built around himself. What impressed me most about this novel was Ferrari’s ability to delineate the awful behaviors and attitudes of men with absurd levels of unchecked power and status. His commentary on materialism and how we identify with what we have had me thinking for weeks after I read this. FSG2020 rocks!

Like Flies From Afar is Argentinian author K. Ferrari’s brutally honest and expletive-ridden murder mystery, translated and published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux in 2020. FSG is an imprint I’ve been tuned to in the recent past, and I have yet to be disappointed by anything of theirs that I’ve taken a chance on, this novel no exception. Like Flies From Afar follows Luis Machi, a delusional Argentinian oligarch fueled by machismo and his cocaine habit, through a downward spiral of paranoia that threatens to dissolve his guise of masculinity. When Machi finds the dead body of an unidentifiable man in the trunk of his spotless BMW, he is forced to confront the realities of the dirty and drug-driven life and identity he has built around himself. What impressed me most about this novel was Ferrari’s ability to delineate the awful behaviors and attitudes of men with absurd levels of unchecked power and status. His commentary on materialism and how we identify with what we have had me thinking for weeks after I read this. FSG2020 rocks!

Alexis Schaitkin’s brilliant debut, Saint X, is far more than a murder mystery or a typical beach-read thriller, though it definitely does both of those justice. This novel, though centered around the death of a young girl, is much more an exploration into race, class, privilege, status, wealth and position in America and specifically, in New York. Beautifully written, Saint X is told from the perspectives of all of those surrounding the murder of Claire Thomas, and Schaitkin is able to believably show and tell each of these characters impressively well. Each first person account and perspective blends into the next; and though these narrators come from far different backgrounds, their mutual telling of the story provides some central truth and understanding. Schaitkin’s unique style comes across incredibly well-realized, and it’s hard to believe this is her debut novel. I can’t wait to read what’s next from her, and if you pick this one up, you’ll feel the same way.

Alexis Schaitkin’s brilliant debut, Saint X, is far more than a murder mystery or a typical beach-read thriller, though it definitely does both of those justice. This novel, though centered around the death of a young girl, is much more an exploration into race, class, privilege, status, wealth and position in America and specifically, in New York. Beautifully written, Saint X is told from the perspectives of all of those surrounding the murder of Claire Thomas, and Schaitkin is able to believably show and tell each of these characters impressively well. Each first person account and perspective blends into the next; and though these narrators come from far different backgrounds, their mutual telling of the story provides some central truth and understanding. Schaitkin’s unique style comes across incredibly well-realized, and it’s hard to believe this is her debut novel. I can’t wait to read what’s next from her, and if you pick this one up, you’ll feel the same way.

Nguyen Phan Que Mai’s powerful family saga, The Mountains Sing, is told across multiple generations within a North Vietnamese family during the 20th century, before, during and after the Vietnam war. A grandmother and her granddaughter serve as the protagonists here, recounting their firsthand experiences of hardships incited by war and imperialism, known all too well by the North Vietnamese. Mai’s prose is pure, authentic and moving, genuine and simple in the best ways. The Mountains Sing offers the invaluable perspective of life lived during a war that has been so misconstrued and misunderstood by Americans since it happened. These characters’ accounts seem vital to the conversation around the Vietnam War, and I’m so fortunate to have read this book and to be able to show it to friends and family. It’s seriously beautiful and important; it’s for everyone.

Nguyen Phan Que Mai’s powerful family saga, The Mountains Sing, is told across multiple generations within a North Vietnamese family during the 20th century, before, during and after the Vietnam war. A grandmother and her granddaughter serve as the protagonists here, recounting their firsthand experiences of hardships incited by war and imperialism, known all too well by the North Vietnamese. Mai’s prose is pure, authentic and moving, genuine and simple in the best ways. The Mountains Sing offers the invaluable perspective of life lived during a war that has been so misconstrued and misunderstood by Americans since it happened. These characters’ accounts seem vital to the conversation around the Vietnam War, and I’m so fortunate to have read this book and to be able to show it to friends and family. It’s seriously beautiful and important; it’s for everyone.

What struck me early on in Deacon King Kong was its similarity in style and prose to Barry Gifford’s Southern Nights and John Kennedy Toole’s classic, A Confederacy of Dunces. I love the way McBride writes; his dialogue and characters are both completely believable and hilarious. Deacon King Kong follows the aftermath of a shooting in a 1960s Brooklyn, NY project called the Cause House — it is captivating and humorous in its most basic forms, but on a deeper level achieves real insight into the history of those who inhabited New York during the 1960s. These are the kinds of characters that follow you around, ones that you’ll nostalgically reflect on from time to time, as if you have real memories of having spent time with them. In a way, I feel like I have spent real time with them, and I’m thankful to have had the opportunity to read this book for that experience alone. You’re in good hands with James McBride!

What struck me early on in Deacon King Kong was its similarity in style and prose to Barry Gifford’s Southern Nights and John Kennedy Toole’s classic, A Confederacy of Dunces. I love the way McBride writes; his dialogue and characters are both completely believable and hilarious. Deacon King Kong follows the aftermath of a shooting in a 1960s Brooklyn, NY project called the Cause House — it is captivating and humorous in its most basic forms, but on a deeper level achieves real insight into the history of those who inhabited New York during the 1960s. These are the kinds of characters that follow you around, ones that you’ll nostalgically reflect on from time to time, as if you have real memories of having spent time with them. In a way, I feel like I have spent real time with them, and I’m thankful to have had the opportunity to read this book for that experience alone. You’re in good hands with James McBride!

Thanks for reading, and thank you for supporting our bookstore. Give us a call at 601-366-7619 for any questions or to buy any of these awesome books! We love you!

Sisters of the Undertow

Sisters of the Undertow A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel,

A native of the Georgia coast, Taylor Brown offers readers his fourth novel,

In

In  Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,  Oxford’s Michael Farris Smith reinforces his rising prominence as “one of Southern fiction’s leading voices” with his newest Southern noir offering,

Oxford’s Michael Farris Smith reinforces his rising prominence as “one of Southern fiction’s leading voices” with his newest Southern noir offering,

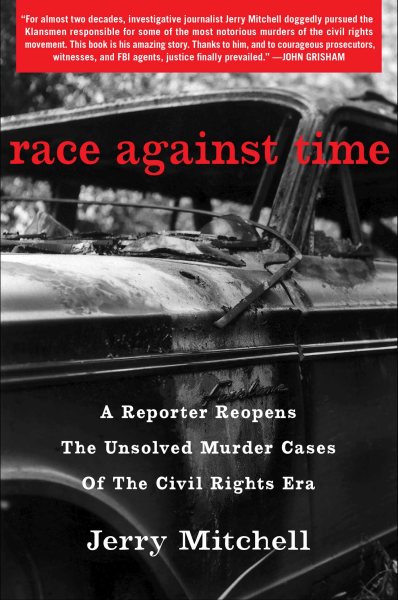

An assignment to cover the press premiere of a movie 30 years ago would bring a decades-old Mississippi murder case back into the nation’s spotlight–and change the life of not only court reporter Jerry Mitchell, but untold numbers of many who thought justice would never come.

An assignment to cover the press premiere of a movie 30 years ago would bring a decades-old Mississippi murder case back into the nation’s spotlight–and change the life of not only court reporter Jerry Mitchell, but untold numbers of many who thought justice would never come.

In

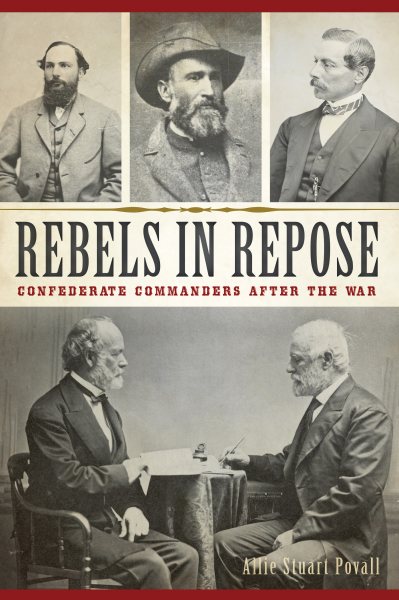

In  Oxford resident and retired attorney Allie Povall’s exploration of what became of many of the South’s major military leaders after the Civil War provides an in-depth–and often surprising–look into their lives after they put down their weapons and left the battlefields.

Oxford resident and retired attorney Allie Povall’s exploration of what became of many of the South’s major military leaders after the Civil War provides an in-depth–and often surprising–look into their lives after they put down their weapons and left the battlefields.