Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (August 13).

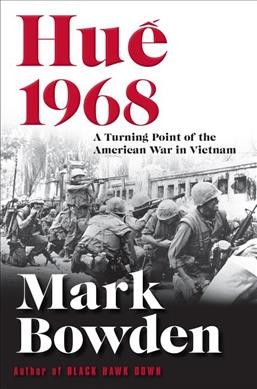

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Grove Atlantic).

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Grove Atlantic).

Nearly 50 years later, the man who is perhaps best known for his blockbuster Black Hawk Downexposes in detail the sense of betrayal Americans felt when the war they had been told the country was handily winning suddenly became the war they could, at best, withdraw from “with honor.”

The author of 13 books, Bowden now writes for The Atlanticand Vanity Fair, among other magazines. He was a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer for 25 years. A native of St. Louis, he now lives in Pennsylvania.

Bowden will participate in the History Makers panel during the Mississippi Book Festival August 19 in Jackson. The event will be at noon in the Old Supreme Court Room of the Mississippi State Capitol Building.

What spurred your interest in writing this detailed historical account of the 1968 Tet Offensive during the Vietnam conflict?

Vietnam has been for me a subject of tremendous interest throughout my life. I was 16 years old when Tet, this battle, happened. Myd ad and I battled about Vietnam then, with me against (the war), him for it, with neither of us having a whole lot of knowledge about it.

So, at a fairly young age, I started reading the newspaper; and, on my own, I subscribed to Time magazine. I would go the library and grab books (about it) at random off the shelf. I started reading sytematically in order to bone up for arguments with my dad about Vietnam. These habits I developed of researching and writing led me to becoming a journalist and writer.

I had never written about Vietnam before. In the epilogue, I talk about how this battle for Hue in the Tet Offensive was a turning point for the American battle in Vietnam–and (Gen. William Westmoreland’s) refusal to fact facts about this, the single most important event in the war.

The more I thought about it, this battle was the sort of dramatic episode that, if I could dig deep into this moment, it could become a lens into the war itself. Hue had all the features of the war–heroism and fears of both the American and Vietnamese soldiers, and politics in Washington that shaped military strategies. It gives a pretty good glimpse of the bigger war.

Explain the historical significance of this event.

The U.S. began investing really heavily in Vietnam in 1964-65. There had been advisers before that who had been helping the Vietnamese government, but it was then that LBJ (President Lyndon Baines Johnson) made the decision to send large numbers of troops.

In 1967, there were half a million American soldiers in Vietnam. The president and Westmoreland were assuring the American people this would be an easy war in this rag-tag little country. Westie had come back to Washington and he gave a speech to the National Press Corps (in November 1967) saying that the war was well in hand and that they were entering the “third phase,” where troops would start returning home.

In January 1968, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched surprise attacks and took Hue, the third largest city in South Vietnam–hardly an offensive by a depleted foe. Hue was a tremendously significant place, as Vietnam’s ancient capital and center of culture and religion.

Clearly, Hue had a n impact on the U.S. and South Vietnam. The South Vietnamese people were caught between communists and the Viet Cong of North Vietnam. Their government and their lives depended on how this war went. And at home, Americans lost confidence in what their leaders were telling them, as their assurance in their own government officials was seriously eroded.

After Tet, (CBS Evening News anchorman) Walter Cronkite, who was called “the most trusted man in America,” at that time, told his viewers, “We’re not going to be able to win,” and that our best hope would be to “negotiate our way out.”

Shortly after, LBJ announced on TV that he would not seek re-election for the Presidency.

Cronkite’s comment was a remarkable thing, but he felt betrayed, like he had been used by American officials. He had been a war correspondent during World War II. He went to Vietnam and came back with his own opinion. His statement (of those opinions on air) was a real departure for a journalist back then, but he felt compelled.

The U.S. had fought in World War II and Korea, but Vietnam was a real blow to that essentially naïve belief that our sheer military strength would prevail, no matter what. Sometimes we go tto war for really bad reasons, and we’re told lies. We’re betrayed by our own government.

Westie continued to have this fixed idea, and did not waiver, in his belief that Hue was not a serious setback.

Hue 1968 is described as your “most ambitious work yet,” and the research you’ve done is amazing. How long did it take to put this book together, and how did you trace all of this history, and in such detail?

It was a very ambitious undertaking. Throughout my career, I’ve always looked for projects with bigger, harder challenges. The nature of journalism is plunging into subject about which you know nothing.

Because of the internet, I learned about finding American soldiers who had fought in Vietnam. Once I could find one or two, I would get an “interview tree” to branch out on. Finding soldiers from the Vietnamese side was different. I realized I needed to hire people who were really good at finding people, and work with them and through them…to find Vietnamese veterans…then I followed up.

I did the traditional things you have to do to be a serious historian. But I am not an academic historian and don’t pretend to be. I visited the LBJ (Presidential) Library in Austin, Texas. I studied Westmoreland’s papers.

My book is based on interviews and memories of people who were there. There are advantages and disadvantages to that–memories are not perfect, but I feel justified in relying on memory. I’ve received unsolicited e-mails of thank from people, for capturing what others did not in this story. A sweet spot for me in the timing of the book is that people are still alive who lived it.

The book took six years. The first steps toward working on this book took place years ago. I began ordering books on the subject, thinking how to go about it. The process is 99% research and reporting in the beginning, then 50/50 reporting/writing, and then 99% writing.

Who should read this book? How can young people today relate to this event, and why is it important for today’s generation to know about this?

It goes to the question of “Why study history?” It has a lot to tell us about successes and failures and how things happen they way they do. I can’t imagine anything more important. It delves into motivation–and mistakes made. As a society, not as individuals, we see how Vietnam has reverberations still today, in its effects on society. It’s a way to continue that good hard look at how we fit in that coherent flow of history.

I would hope that everyone should read this book. It’s not just for a military audience or academic historians. And for all those reasons, it’s a compelling story.

Do you have family or other connections to Vietnam and to this war?

No connections. None of my brothers served in Vietnam. I had some uncles who served in Korea and World War II. No cousins. I knew people in high school and college and throughout my life who served in Vietnam. I grew up living with the Vietnam war in my house and arguing with my dad about it.

Is it true that Hue 1968 will be produced as a television mini-series?

It’s already in the works. It’s set to be a 10-part mini-series on FX, with Michael Mann as the producer/director. That work is just beginning. I’m excited about it!

Mark Bowden

What’s your next writing project/book?

I have the cover story on The Atlantic this month (on what to do about North Korea). A Vanity Fair story. I kind of deliberately don’t have a book project now. I like to have time in between books. But ask me again at the end of the year!

Hue 1968 is Lemuria’s August selection for its First Editions Club. Mark Bowden will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival first at 12:00 in the Old Supreme Court Room with Howard Bahr, author and Vietnam veteran. He will also be interviewed with U.S. Representative Trent Kelly at 4:00 in State Capitol Room 201H about the Vietnam War.

Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel, The Sorrow of War, is one of the only pieces of Vietnam War literature to make it out of Vietnam.

Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel, The Sorrow of War, is one of the only pieces of Vietnam War literature to make it out of Vietnam. First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995.

First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995.

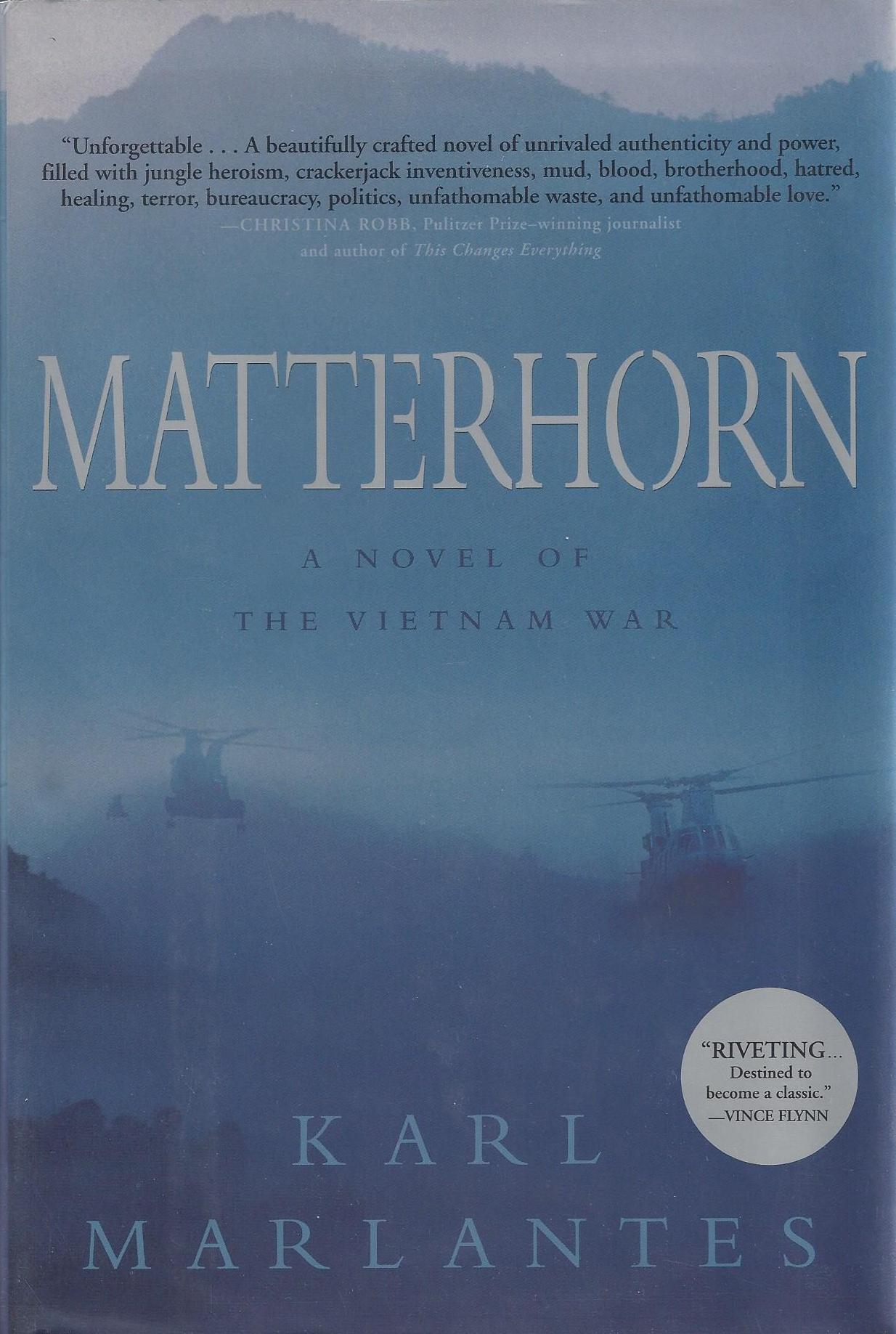

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype.

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype. This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line.

This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line. Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release

Author and journalist Mark Bowden challenges a new generation of readers to question America’s involvement in Vietnam as he examines, with laser precision, the bloody battle for the city of Hue (pronounced “whey”) in his newest release

These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,

These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,  With Candice Millard’s latest biography

With Candice Millard’s latest biography

As editor of the Richmond News Leader, Freeman spends the next few hours organizing, composing letters and World War I editorials. By 8:00, it is time for his daily radio broadcast, then the daily conference with the newspaper staff. At noon, a nap. By 2:30, he turns his attention to his life’s work: writing the multi-volume biography of Robert E. Lee. Freeman settles to bed at 8:30 to begin the next day with the same intensity. With these details meticulously documented in David Johnson’s biography of Freeman, it’s not surprising that Freeman wrote late in life that he expected “to die with a pen in [his] hand.”

As editor of the Richmond News Leader, Freeman spends the next few hours organizing, composing letters and World War I editorials. By 8:00, it is time for his daily radio broadcast, then the daily conference with the newspaper staff. At noon, a nap. By 2:30, he turns his attention to his life’s work: writing the multi-volume biography of Robert E. Lee. Freeman settles to bed at 8:30 to begin the next day with the same intensity. With these details meticulously documented in David Johnson’s biography of Freeman, it’s not surprising that Freeman wrote late in life that he expected “to die with a pen in [his] hand.”