Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (August 25)

Slovenian attorney Margerita Jurkovic said she had “no idea what to expect” when she arrived in Jackson in 2017 as a law exchange student–but it wasn’t long before she found herself captivated by a passion for a brand new experience: American (and specifically Southern) football.

She soon realized that the stories she lived out as she discovered the thrill of the game, literally on the sidelines, were the stuff that would make a good read, and Margerita’s Gridiron Adventure: A Slovenian Lawyer’s Crash Course in American Football Culture was the inevitable outcome.

She soon realized that the stories she lived out as she discovered the thrill of the game, literally on the sidelines, were the stuff that would make a good read, and Margerita’s Gridiron Adventure: A Slovenian Lawyer’s Crash Course in American Football Culture was the inevitable outcome.

Mike Frascogna, a Jackson attorney and former law professor of Jurkovic’s, took the football novice under his sports-driven wing and introduced her to the game at youth, high school and college matches throughout the Southeast during the 2018 season. Her perspective, as an outsider who was new to the game–and the culture–of Southern football is honest, humorous, and often thought-provoking.

Jurkovic received her second Master of Law at Mississippi College in 2018, graduating magna cum laude. She also holds a doctoral degree in criminal law and human rights. In Slovenia, she serves as CEO of a non-profit organization that works with victims of domestic abuse and human trafficking.

While in Mississippi, Jurkovic specialized in negotiations and entertainment law at Frascogna Entertainment Law, a Division of Frascogna Courtney, PLLC, in Jackson.

What brought you to Mississippi from your home country of Slovenia?

Margerita Jurkovic

First, it started as an educational experience in law for me. Finishing my PhD, I thought it would be useful to get some experience in a country with a common law system, so I found Mississippi through one of my law school contacts at home. I was planning on staying only a couple of months, but before I realized I had been in Jackson for almost two years.

How did your passion for Mississippi football develop so quickly, and what role did Jackson attorney Mike Frascogna play in that process?

It happened so spontaneously, my passion for football. While in Jackson I was constantly surrounded by people who are interested in this sport. Seeing the enthusiasm of players and coaches, and then experiencing what the win of their chosen teams means to the fans (played a big part) . . . and Mike Frascogna–he knows a lot of people around here. I learned a lot from him, not only football, but about the law, and also life.

It seems you had a unique vantage point at the high school and college football games you attended during your time in Mississippi: you were actually on the sidelines during the games! How was Mike able to make that possible, and do you think that made the games even more exciting, especially since you usually got to meet the coaches or high-level school officials?

Absolutely–I got to experience things most fans cannot, and this is why the book has so many unique stories–like hearing the pre-game talks in the locker rooms. I became spoiled in a way–now, I only want to watch football from the sidelines! The involvement of the Frascogna law firm in Mississippi athletics made things easier for us. One of my characters in the book said, “Mike can make anything possible!” I guess she was not far from the truth.

What were some important lessons you learned from this experience?

There are many lessons one can learn while living abroad, especially how to keep yourself happy and involved in local activities, even while being so different, and often missing home. There are many differences between European and American life, but we all share the same human needs. Seeing the 7- and 8-year-olds playing the rough sport of football helped me understand some basic American values: protecting teammates, loving competition, and not being afraid of physical contact.

What convinced you to write a book about this adventure?

I did not need any convincing after coming in contact with the passion of the coaches and players for the game, and observing the enjoyment of the fans, cheerleaders, bands and the dance groups. It is truly a unique cultural event, involving the entire community. The emotions of this sport got me from the first day.

I never expected that I would be writing a book about football, surrounded by sweet tea and strong men, seriously fighting out there, for the love of the game.

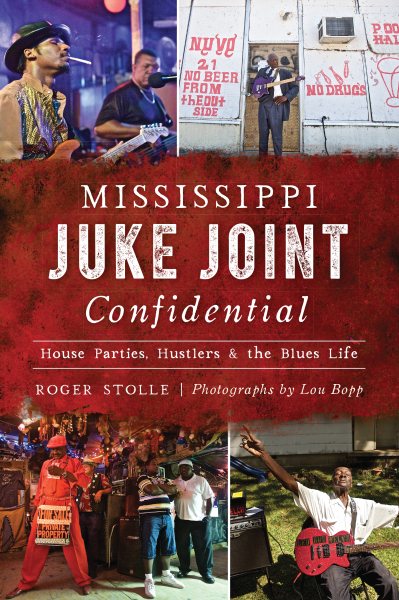

Early in the millennium, Stolle moved from St. Louis to Clarksdale to open Cat Head music shop. Since then, he has gone on to start the annual Juke Joint Festival, produce several artists’ records and tours, become a contributing editor for Delta Magazine, deejay locally and on satellite radio, helm a trio of blues documentaries (We Juke Up In Here, M is for Mississippi, and Hard Times) and host the web series Moonshine and Mojo Hands.

Early in the millennium, Stolle moved from St. Louis to Clarksdale to open Cat Head music shop. Since then, he has gone on to start the annual Juke Joint Festival, produce several artists’ records and tours, become a contributing editor for Delta Magazine, deejay locally and on satellite radio, helm a trio of blues documentaries (We Juke Up In Here, M is for Mississippi, and Hard Times) and host the web series Moonshine and Mojo Hands.

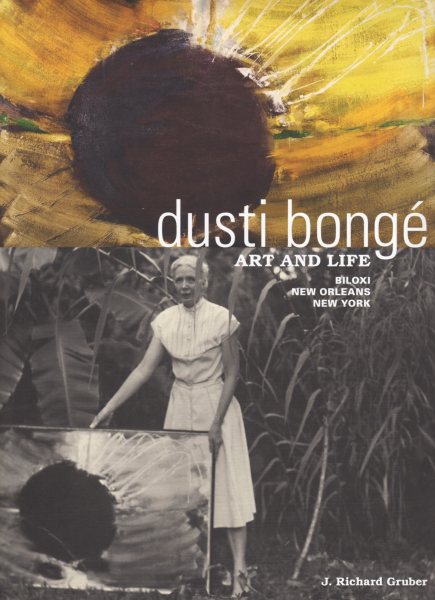

In the interest of full disclosure, let me state that I know Rick Gruber, and I know him to be a scholar of the first order who has at his command more information about art of a southern nature than anyone alive. It is also worth noting that his prose is infinitely readable, unlike so many of those who write about art in a scholarly fashion.

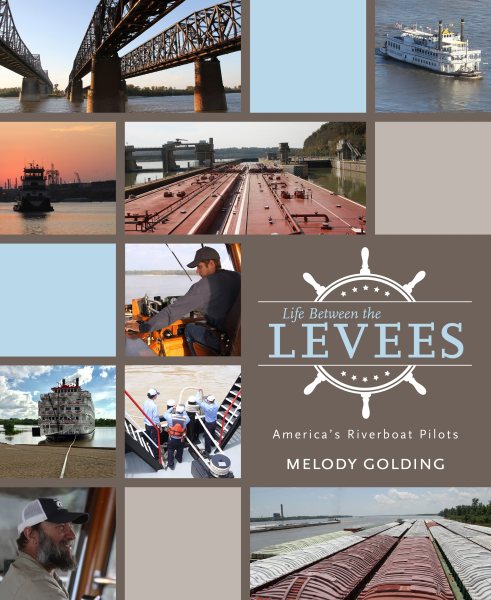

In the interest of full disclosure, let me state that I know Rick Gruber, and I know him to be a scholar of the first order who has at his command more information about art of a southern nature than anyone alive. It is also worth noting that his prose is infinitely readable, unlike so many of those who write about art in a scholarly fashion. One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book,

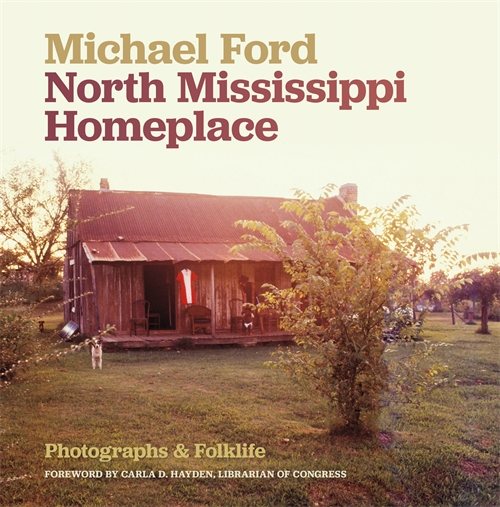

One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book,  Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “

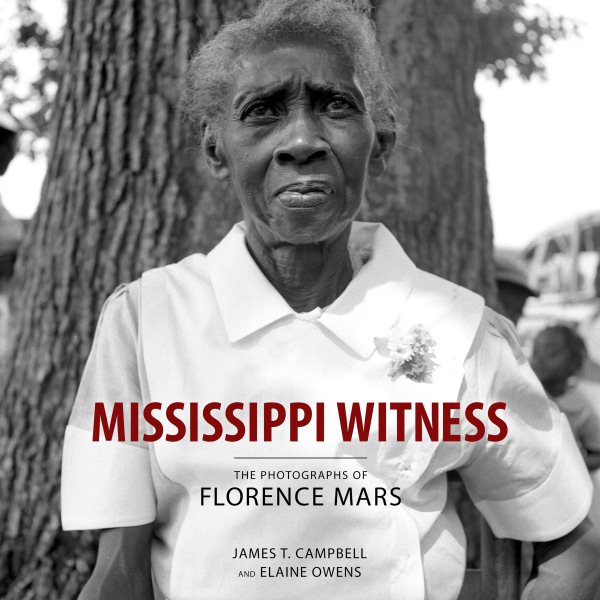

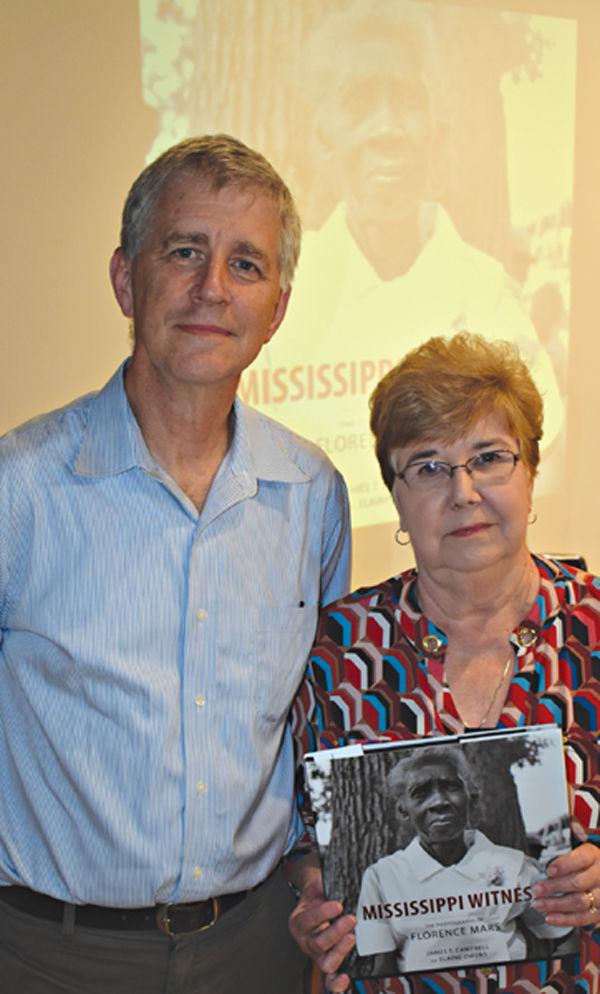

This is what bestselling author and Alabama native Helen Ellis calls “ Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

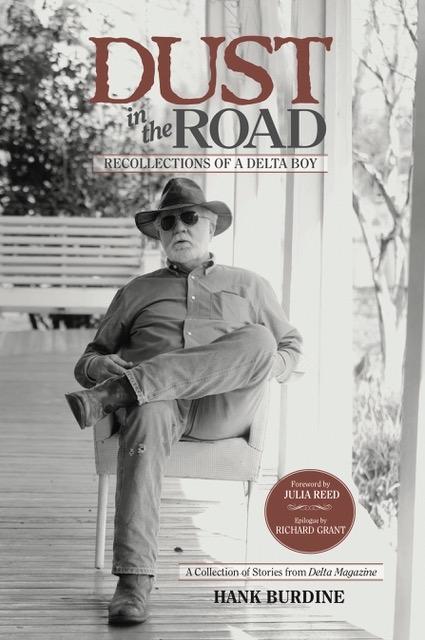

The gentleman farmer, road builder, and author, who has gained a reputation as “the historian of the Delta,” has bestowed upon his fellow Deltans–and the rest of the world–a gift of memories and stories that may otherwise have been lost, with his newest book,

The gentleman farmer, road builder, and author, who has gained a reputation as “the historian of the Delta,” has bestowed upon his fellow Deltans–and the rest of the world–a gift of memories and stories that may otherwise have been lost, with his newest book,