Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 7)

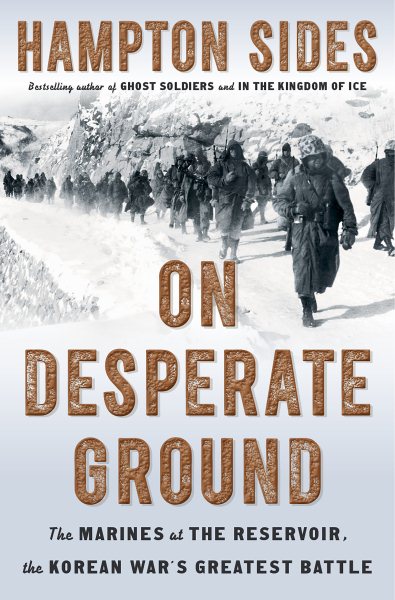

Author-journalist Hampton Sides brings his readers yet another true–but almost unbelievable–high-stakes account of grit and courage with his newest work, On Desperate Ground: The Marines at the Reservoir, the Korean War’s Greatest Battle.

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

Through his meticulous research that includes declassified documents, unpublished letters and interviews with scores of survivors on both lines, Sides presents a “grunt’s-eye view of history” as he shows “what ordinary men are capable of in the most extreme circumstances.”

His previous books include Ghost Soldiers, Blood and Thunder, Hellhound on His Trail, and In the Kingdom of Ice. An award-winning editor for Outside magazine, Sides’ Ghost Soldiers also captured the PEN USA Award for Nonfiction.

A native of Memphis, Sides is a graduate of Yale University and teaches narrative nonfiction at Colorado College.

Since you grew up in Memphis, do you have ties to our state?

Yes. I have deep roots in Mississippi, actually. I have lots of relatives from around Holly Springs. My dad taught at Ole Miss law school. Some of my best early journalism was done in the state. And I always love getting back to the Delta, which just has a certain vibe about it that I’ve always loved.

Throughout your writing career, your books and journalistic works have focused on a steady stream of real-life–and often high-risk–tales of adventure, discovery, exploration, and the great outdoors, not to mention war and other profound historical narratives. Tell me how you developed your appetite for these bold themes.

Hampton Sides

Probably my interest in these types of stories grew out of my years as an editor at Outside magazine, which over the years has run some of the very best adventure and sports writing in the country. When I was on staff there, I got to work with some of the preeminent writers in the country, who gave me some terrific ideas about how to make writing vivid and muscular, and how to make things come alive on the page.

I decided to go back into history and hunt for some of those same qualities that we were looking for at Outside. Many of my books have focused on the larger theme of human endurance–how people survive terrible ordeals, summoning some combination of courage, ingenuity, and grace under pressure. It’s a powerful motif, and one I seem to keep returning to.

On Desperate Ground is an account of the almost unbelieveable efforts of the U.S. Marines during a pivotal battle in the Korean conflict of the 1950s. Considering the substantial investment of your time and effort, how do you make decisions on topics to write about–and how did this story catch your attention?

Years ago, at a book signing in Virginia, I met a grizzled old veteran of the battle. With a hand that was missing a few digits from frostbite, he slipped me this card that said “The Chosin Few.” He said I ought to write about it someday. Honestly, I’d never even heard of the Chosin Reservoir. I put the card in my pocket and didn’t think about it for many years.

When I finally started looking into the battle, I realized it was one of the most harrowing clashes in our history, a remarkable feat of arms. I thought it should be better known. Here, it seemed, was the ultimate military survival story. Finally, with all the recent developments in our relations with China and the two Koreas, I felt that was an auspicious time to tell this classic story.

Many readers will no doubt be surprised to read your portrayal of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, disclosed in this book through his actions and attitudes. Describe the man your research revealed.

In 1950, Douglas MacArthur was a famously arrogant man and a glory hound at the height of his power, but he was criminally out of touch with reality. He ignored clear evidence that vast numbers of Chinese had entered North Korea to spring a trap and prepare a surprise attack.

He presided over one of the most egregious intelligence failures in American military history. And once the intelligence came in loud and clear, he and his staff of sycophants chose to ignore it, suppress it, or willfully misinterpret its import. In so doing, they needlessly put many tens of thousands of Americans in harm’s way. In my mind, he has a lot of blood on his hands.

You write in the book that the soldiers who survived this horrific, bitterly cold battle were “different men” when it was over. What can you tell me about your interviews with actual survivors of this battle.

At Chosin, the mercury dropped to 20 below zero, sometimes even lower. Many weapons wouldn’t fire. Lots of guys froze to death. The weather claimed more casualties than the combatants did. More than 80 percent of these men suffered severe frostbite. Many lost fingers and toes. Some of them told me they still feel the cold., that they never did quite thaw the chill from their bones.

All battles are terrible, but this one was fought under such extreme conditions, on such forbidding terrain, in such insane weather, and against such overwhelming numerical odds, that it takes a special place in the annals of combat. It’s one of the most decorated battles in our nation’s history, and with good reason. The extremity of the ordeal brought to the fore a naked survival instinct, a fierce camaraderie, and a rare improvisational spirit.

And yet, because i twas in the Korean War, much about their experience has been forgotten. I know a lot of these veterans are resentful of the fact that their experiences and sacrifices seem to have been largely ignored by so many of their countrymen and given short shrift in the history books.

The current, developing relationship between North and South Korea, along with the role of the United States, has been in the news a lot lately. Can you share your thoughts on their progress, and what you may see in their future?

I recently spent time in South Korea, and I was heartened by what I saw and heard. I could feel a certain energy in the air, almost like we saw in Germany before the wall came down. I know that President Trump likes to take credit for these developments, but the desire to improve relations between the two countries is much, much bigger than any one individual. I think what we are seeing is largely an organic phenomenon of the people, not one that’s particularly being driven by the U.S., China, or any other power.

Of course, Korea should never have been divided in the first place–it is one of the great tragedies of modern times. Many, many thousands of families were torn apart and never were allowed to see each other again. Korea is one people, one language, one culture, and I believe one day it will be united again.

Are you already working on another book or other project, and, if so, what can you tell me about it?

My next book, tentatively titled The Resolution, is about the final fateful voyage of the British explorer, Captain James Cook. It takes place during the American Revolution, and I plan to give the story a uniquely American slant. I’ve just begun the research, which will take me from Tasmania to Kamchatka, from the Bering Strait to Tahiti, with lots of time in Hawaii and the archives of London. In the end, it’s a story of far-flung exploration, and a tragic collision of cultures in Polynesia. It will keep me busy for years, and I can’t wait to get started.

Hampton Sides will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, October 10, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from On Desperate Ground. On Desperate Ground is Lemuria’s October 2018 selection for our First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

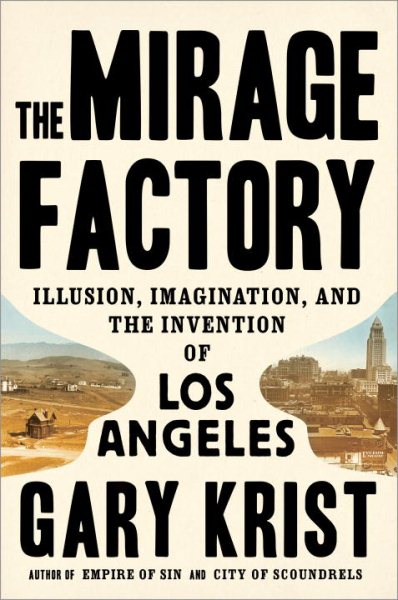

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

Gary Krist’s fascinating account of the history of Los Angeles during the first three decades of the 20th century puts a highly personal face on the mage-city’s early days through the almost unbelievable stories of three of its most interesting and important influencers in

In

In  Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

Although the settlers were on a mission to establish the first English colony in the New World, they disappeared without a trace while their leader was away on a six-month resupply trip that had stretched into three years. They left only one clue–a “secret token” carved on a tree.

His newest book,

His newest book,

On November 13, 2015, the world watched in horror as terrorists attacked Parisians going about life at football matches, concerts, dinners, time spent with friends and family. Journalist Antoine Leiris lived another horror that night: turning on the news and seeing that the Bataclan Club, where his wife was attending a concert, had been attacked. In

On November 13, 2015, the world watched in horror as terrorists attacked Parisians going about life at football matches, concerts, dinners, time spent with friends and family. Journalist Antoine Leiris lived another horror that night: turning on the news and seeing that the Bataclan Club, where his wife was attending a concert, had been attacked. In  A few years ago, AFJ was fortunate to host Memphis historian for a program based on his book,

A few years ago, AFJ was fortunate to host Memphis historian for a program based on his book,  As a Francophile graphic designer who spends most of her reading time studying World War II,

As a Francophile graphic designer who spends most of her reading time studying World War II,

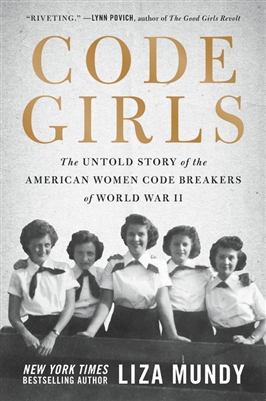

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1945. The United States was caught virtually unawares, in a nearly two decade season of disarmament. The U.S. military had sparse forces, and few spies abroad. There was an immediate and urgent need for code breakers to decipher enemy message systems.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1945. The United States was caught virtually unawares, in a nearly two decade season of disarmament. The U.S. military had sparse forces, and few spies abroad. There was an immediate and urgent need for code breakers to decipher enemy message systems.