By Matthew Guinn. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 14)

The American canon just got a new addition.

Karl Marlantes’ sprawling Deep River deserves no lesser estimation. It echoes the sweep of his contemporaries Toni Morrison and Jim Harrison at their best, but also harkens back to the epic naturalist novels of Jack London and Frank Norris. And in singing the beauties and perils of the American landscape, it has few equals in any era of our literature. Deep River is a new American classic.

Karl Marlantes’ sprawling Deep River deserves no lesser estimation. It echoes the sweep of his contemporaries Toni Morrison and Jim Harrison at their best, but also harkens back to the epic naturalist novels of Jack London and Frank Norris. And in singing the beauties and perils of the American landscape, it has few equals in any era of our literature. Deep River is a new American classic.

Fitting that Deep River is a tale of immigrants, folk from old lands seeking a new one, and that it spans not only two continents, but two centuries. In this case, it is a Finnish family, the Koskis, tenant farmers suffering under the brutal Russian occupation of Finland. The oldest Koski brother has already immigrated to Washington State. His letters home tell of logging trees so gargantuan they must be seen to be believed by European eyes, of freedom from serfdom, and of bountiful, good-paying work.

By a turn of events the reader cannot anticipate, his sister Aino is the next Koski to follow him to America. The novel coheres around Aino even as Marlantes adds in scores of vivid characters—Finns and Swedes—who form a tight-knit immigrant community logging and fishing Washington State. Reaction is mixed to the brand of socialism Aino brings with her from the Old World and trouble finds her again. And again.

Aino is surely the most exasperating heroine in American literature. Time after time, she helps turn a good situation bad by her dogged agitation for the dream of socialism and the “Wobblies” labor party. People are hurt by her, and she leaves a wake of damage behind at every stage of her life. In matters of love, one never knows which way her heart will lead her. And yet we follow—exasperated, intrigued—because she is enigmatic, unpredictable, totally alive. She is as fully human—that is to say, complex and fallible—as we are. She is the lightning rod to whom all her fellow characters respond.

Yet Marlantes is careful and adept not to let Aino dominate his story. If there is a single dominating force in the novel, it is work. One is hard pressed to name a novel that has celebrated labor so eloquently. Deep River is a paean to the joy, dignity, cunning, and stamina of skilled physical labor and the men and women who perform it. Our digital century tends to forget the artistry required to bring down a 300-foot tree precisely by hand, or the intuition needed to read the currents on a river to determine where fish are running. Marlantes reminds us.

He also reminds us how thoroughly women and Native Americans contributed to forming America, and on this point it is clear how much Deep River adds to our national literature. So many of the classic novels of American experience are boys tales told for grown men that dismiss the contributions of women or neglect them entirely. Marlantes gives careful attention to the dignity of what used to be called “women’s work” and the skill and grace it requires, to say nothing of the harrowing experience of childbirth in the early years of the twentieth century. The senior Koski brother could never have built his empire without the guidance of Vasutati, the native healer who reminds him that “constant change” is in fact “life everlasting” and is such a vital force she is able to flirt with him even in death. All of the Pacific Northwest is here, fully represented. All work is honored.

In Deep River, Marlantes is after the whole tapestry of American experience, and he comes closer to getting it than any writer before him. And running counter to the blasé petite-nihilism of our postmodern moment, he reminds us that though life is hard, it is also good. His characters never say aloud that there can be dignity in struggle, meaning in pain. They live it, on every page. Could any worldview be more American?

“What a country this is,” one of the Koskis exclaims at a moment of opportunity seized. What a country, indeed. And what a novel to sing its epic song.

Novelist Matthew Guinn earned his Ph.D. in American Literature at the University of South Carolina. He is associate professor of creative writing at Belhaven University.

Karl Marlantes will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, August 14, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Deep River. Lemuria has chosen Deep River as its August 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

* * *

Marlantes will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival August 17 in conversation with Kevin Powers and Tom Franklin at 12:00 p.m. in State Capitol Room 113.

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned.

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned. Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,

Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,  Mamta Chaudhry’s busy career has taken her from TV and radio stints to published fiction, poetry and feature writing, and with the release of her debut book,

Mamta Chaudhry’s busy career has taken her from TV and radio stints to published fiction, poetry and feature writing, and with the release of her debut book,

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut  As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

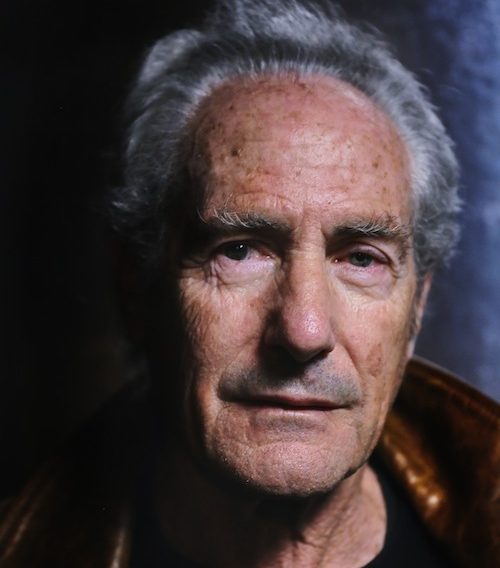

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing. “My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

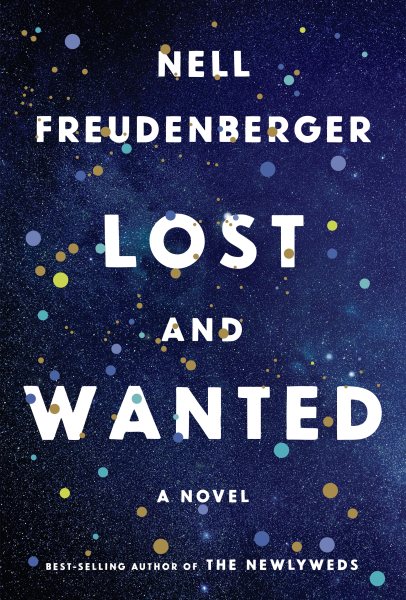

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.